Consider becoming a paid subscriber. I will donate all proceeds to Gaza.

Plan Camelot: Higher Education and Counterinsurgency

In 1962, 90 percent of United States federal funding allocated to the sciences was directed toward military research (Wschebor, 1970, Imperialismo y la Universidad). As Mario Wschebor notes, all the disciplines, including the social sciences, were heavily funded by the Department of Defense, the Atomic Energy Commission, and the Office of Naval Research, ranging from biology and geology to anthropology and sociology. As the author notes, the ‘“success of science’ has been absolute insofar as the results of this particular form of intelligence, placed at the service of the empire, have been used for multiple and complementary purposes. The empire has acquired the necessary flexibility to extend its reach to the most heterogeneous forms of knowledge, in both style and content, and to appropriate them in order to turn them into useful objects for its purposes” (p. 14). Wschebor recognizes that the university, particularly in Latin America, has simultaneously been a space of insurgency but also one that adapts and aligns itself most efficiently to imperial and neocolonial designs.

Academic collaboration with military, paramilitary, and imperial interests was certainly prevalent during the socalled Cold War, referred more accurately by the Zapatistas as the Third World War. The CIA initiated Plan Camelot in 1965 to more effectively infiltrate universities in governance, curriculum, and knowledge production. Irving Horowitz, who published a book on Plan Camelot, explicitly describes the counterinsurgent aims of the CIA’s initiative to restructure education. Plan Camelot, as he put it, “was a project to measure and predict the causes of revolutions and insurgencies in underdeveloped areas of the world. It also sought to find ways to eliminate those causes or to confront revolutions and insurgencies. Project Camelot was sponsored by the U.S. Army and was a contract worth between four and six million dollars with the Special Operations Research Office (S.O.R.O.). This agency is formally under the aegis of the American University in Washington, D.C., which conducts a wide range of research for the military” (as cited by Wschebor, p. 17).

Within the context of the 1960s, after the Cuban Revolution and the resurgence of insurrections, liberation movements, and anticolonial/antiimperial struggles, Latin America was perhaps impacted the most by Plan Camelot. Interestingly enough, the CIA conceived of Plan Camelot’s aims to systematic transform higher education in Latin America as the “profilaxis to insurrection”, one that would foreclose the possibility of an insurgency to emerge, determining in other words what type of social movement could or could not exist within the framework of liberal democracies. Although the CIA discontinued Plan Camelot in 1965, the Center for Research in Social Systems initiated analogous research projects, some of which were focused on the systematic examination of theories that inform revolutionary action in the Global South. Other projects focused on the material and ideological conditions under which insurrections articulated themselves into revolutionary political projects.

Since World War II, knowledge production and positivist methodological techniques, primarily statistical models, were used to study the behavior and reaction to particular policies in any given society. How, in other words, do societies react differently toward structural changes led from above. Comparative analyses informed the varying ways certain societies and social classes reacted to counterinsurgency, allowing thus for its modification and refinement. The Advanced Research Project Agency (ARPA), founded in 1958, was primarily responsible for examining the relationship between material conditions, policies, and social responses to change initiated from above. These studies offered the CIA a better understanding of how to effectively suppress insurrections in the socalled Third World. In collaboration with Georgetown University, ARPA published the following study in 1964: “A Historical Survey of the Patterns and Techniques of Insurgency Conflicts in Post-1900 Latin America.”1 In the opening paragraphs, one gets a sense of the study’s purpose, which was to obtain information that would help the U.S. plan military “R&D requirements for counterinsurgency operations in the area” (ii). One immediately notes the direct relationship between academic research and military strategic development projects that targeted any form of insurgency, including protests and militant action. This study claims that, from 1946 to 1963, over 3,500 insurgency events in Latin America were analyzed. Insurgency is understood in the broad sense, including all “violent actions against governmental authority short of civil war” (vi). The Latin American insurgency environment, as the study labels it, is drastically different from the actions unfolding within the US context at the time. It “exhibits patterns of violence for which no adequate parallels exist in U.S. society or in most societies of western Europe” (ibid). An interesting comparison is made between insurgency in Vietnam and insurgency in Latin America. The study observed that the former’s rural clandestine organization and collective action was more successful than the latter’s structured “organization, discipline, and a sense of planned persistent action” in urban and rural areas, which resulted in “violent outbursts” rather than in a “protracted struggle” (Ibid). Making direct connections with the Cuban Revolution, the study demonstrates that insurgency found more favorable conditions for guerrilla warfare in rural areas than other countries in Latin America, which was later complemented by urban guerrilla warfare.

According to the study’s findings, Latin American insurgency in the early 20th century can be categorized into two primary types: social insurgency and political insurgency. Social insurgency consists of forms of social violence that is residual or quite isolated in other Western societies. These manifestations include spontaneous mass violence, particularly in major urban centers, which can escalate to disrupt social order and have great significance for insurgency. Peasant movements occupying unused land also tend to complement social insurgency unfolding in urban areas. These movements hold the potential to evolve into extensive social upheavals. Political insurgency, on the other hand, takes place primarily through urban protests, riots, labor strikes, military barracks revolts (cuartelazos), and coups, which, as the study suggest, were not as as effective in the region when dissociated from rural struggles. Perhaps it is best to conceptualize social insurgency as subversion, action that anticipates a more militant insurrection.

The above study argues that, prior to Fidel Castro’s revolutionary success in Cuba, guerrilla warfare was rarely used for social or political insurgencies in Latin America. The Cuban Revolution marked a paradigm shift in guerrilla warfare, setting a precedent for subsequent revolutionary movements in the region. In the 19th century, insurgency in Latin America was dominated by rebellions lead by “caudillos” who ultimately were suppressed by the professionalization of the military, which was a result of US and European training missions. By replacing the former, the latter played the role in suppressing various kinds of insurgencies. In the case of the 1973 coup in Chile, we see how the military led by Pinochet played a central role in violently repressing the socialist option in the country through systematic abductions, torture, arrests, disappearances.

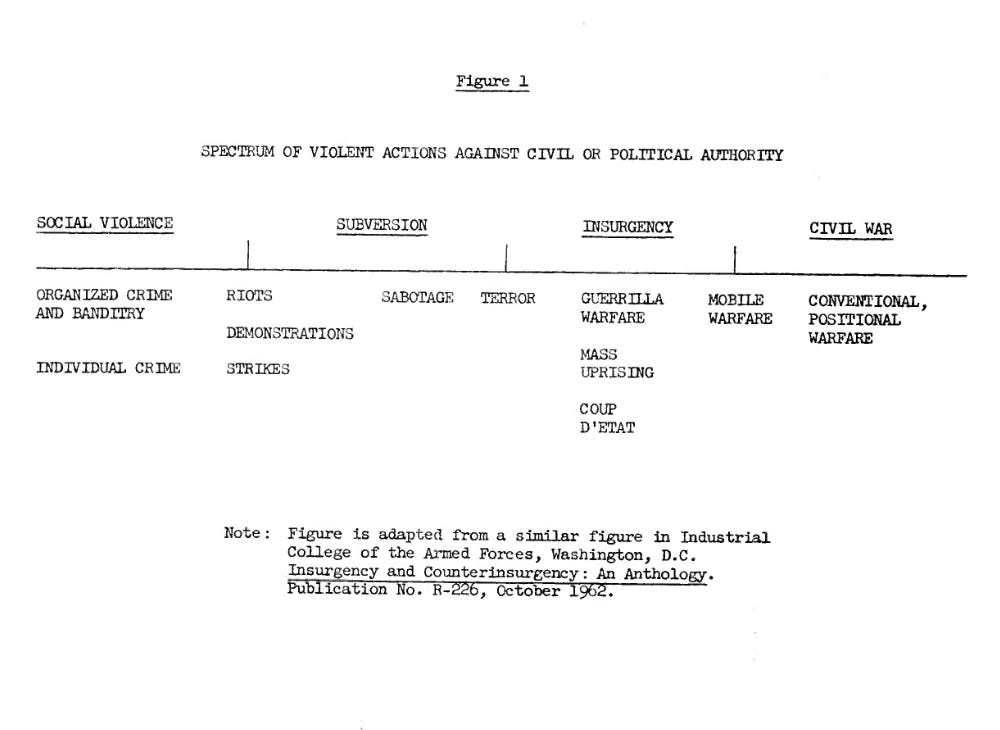

While the forward of ARPA’s historical survey of Latin America focuses more on key examples of insurgency in the region and its distinction from other forms of insurrection, the introduction gives a clearer conceptualization of insurgency and counterinsurgency. The authors of this study recognize that insurgency can carry different meanings depending on the context. As they assert, some may believe insurgency can be equated to guerrilla warfare or revolutionary action, while others may find insurgency to be synonymous to violent action against the State. These can be expressed in multiple forms such as urban and rural social movements’ direct actions that do not always translate to revolutionary action. The study cites the U.S. government’s definition to build upon its key features: “A condition resulting from a revolt or insurrection against a constituted government which falls short of civil war.” The level and scale of violence seems to be the primary criteria to characterize and distinguish insurrections from other forms of civil unrest and collective action that does not seek to articulate itself into a broader revolutionary movement. The spectrum below demonstrates not only the US’s military’s understanding of insurgency but also how social violence can be understood as an emerging form of resistance against authority. Prisons play a central role in counterinsurgency in that they capture those who are most prone to engage in practices that further subvert authority, which as the chart shows, may lead to greater forms of insurgency, guerrilla warfare, and mass uprisings. George Jackson’s, Orisanmi Burton’s, and Dylan Rodriguez’s publications on this topic illustrates this point exactly, while also showing how prisons become spaces of insurgency in their own right.

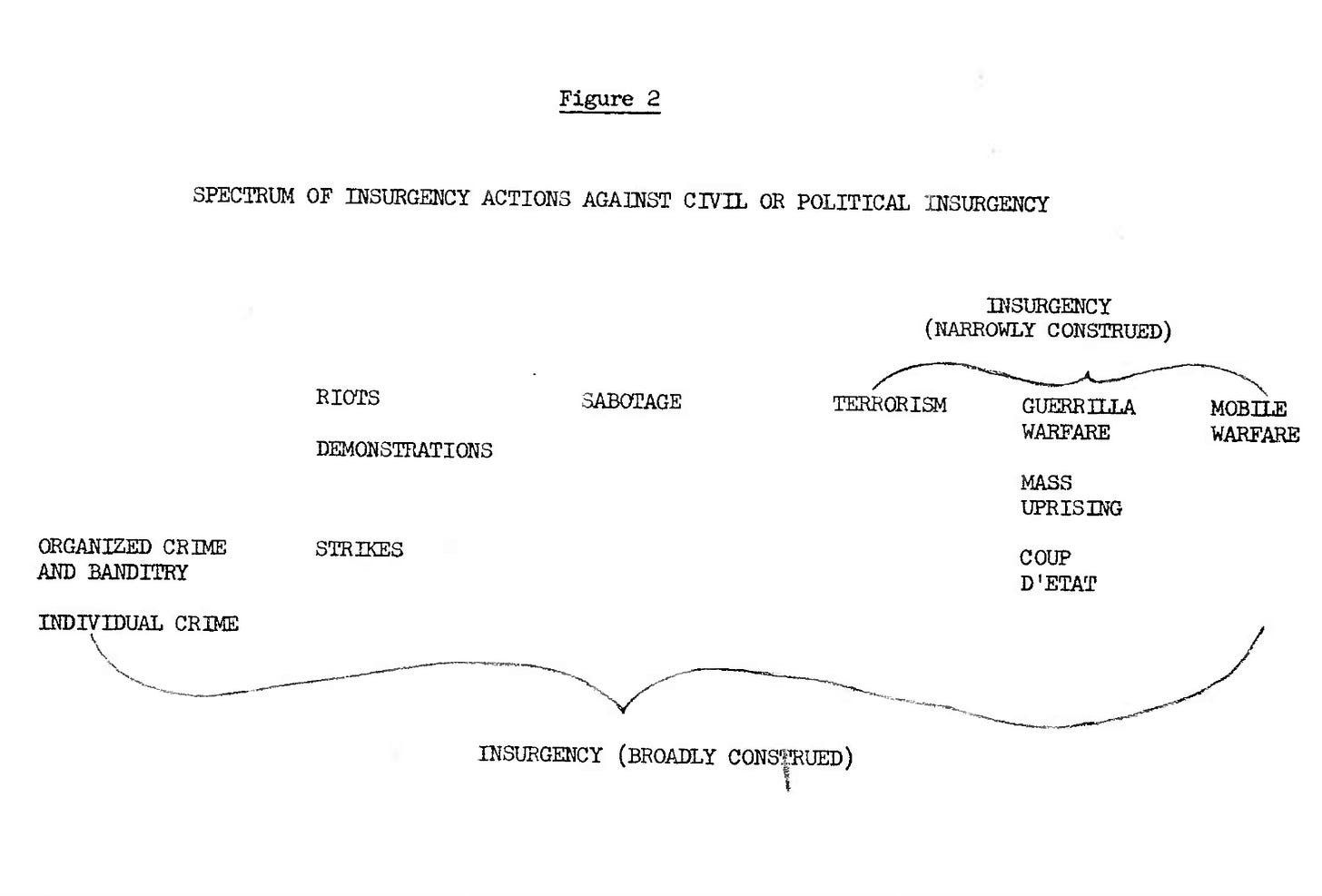

The authors of this historical survey of insurgency seem to disagree, however, with the narrow conceptualization of insurgency, providing a modified chart that maps insurgency more broadly, whereby individual crime or banditry falls within the spectrum of insurgency. The latter conceptualization understands criminal activity as passive resistance that must be studied as well, especially if there is a connection between social violence and large scale guerrilla warfare. The study suggests that, if insurgency is to be understood in its totality, low levels of social violence must be researched seriously for military research and development planners to implement counterinsurgency efforts effectively and precisely. This would then allow for more effective and deliberate use of military or police counterinsurgency, whereby social violence and subversion may more adequately be targeted by the police1 and criminal courts while more militant insurgency can be targeted by the military. A broad conceptualization of insurgency, the authors argue, will “facilitate an understanding of an important strategic problem in Latin America: the problem as to whether the underlying insurgency patterns in the area are such that subversive insurgency will be most likely to draw its strength from rural guerrilla bases in the manner prescribed by Mao Tse-tung, Vo Nguyen Giap, and Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. While no final answer to this problem is possible, it will at least be evidenced by the ensuing broad discussion that the military planner confronts a greatly different environment for insurgency in Latin America than has previously been experienced in other world areas” (p. 7). The real danger thus lies in a strong base in rural campesino, Black, and Indigenous communities that have been the greatest victims of colonialism and racial capitalism.

As we can already observe, there is a long history of anti-colonial insurgency linked to the imperial university. This history serves as the background to understand the shifting ways those in power conceptualize insurgency and counterinsurgency in different contexts. If we fast forward to more recent conceptualizations of (counter)insurgency during the Post-9/11 era and the Global War on Terror, there seems to be an increased attention to researching the emergence of insurgencies and implementing counterinsurgency measures. It’s worth citing at length the Field Manual (2018) published in collaboration with the Department of the Army, the Department of the Navy, and the Marine Corps Combat Development Command. Insurgency is defined as

“the organized use of subversion and violence to seize, nullify, or challenge political control of a region…. The term insurgency can also refer to the group itself. Insurgents can combine the use of terrorism; subversion; sabotage; other political, economic, and psychological activities; and armed conflict to achieve its aims. It is an organization political-military struggle by a predominantly indigenous group or movement designed to weaken, subvert, or displace the control of an established government for a particular region. Each insurgency has its own unique characteristics, but they typically include the following common elements: a strategy, an ideology, an organization, a support structure, the ability to manage information, and a supportive environment. These characteristics present a significant threat to the existing government. Insurgents will typically solicit, or be offered, external support or sanctuary from state or non-state actors” (p. I-1, emphasis added).

Since insurgency is organized in a clandestine manner, counterinsurgency uses various means to infiltrate, delegitimize, and “pacify” groups in order to prevent them from becoming a broad-based revolutionary movement. The cultural and psychological dimensions of counterinsurgency are crucial since they are the cornerstone holding the legitimacy of a State together. More on this below.

In an earlier publication (Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies, 2014), one finds another description of insurgency that should be considered since it sheds light on the material conditions that give rise to militant resistance. Here, the US military conceptualizes an insurgency as a militant group that seeks to

“control and influence, generally from a position of relative weakness, outside existing state institutions. Insurgencies can exist apart from or before, during, or after a conventional conflict. Elements of a population often grow dissatisfied with the status quo. When a population or groups in a population are willing to fight to change the conditions to their favor, using both violent and nonviolent means to affect a change in the prevailing authority, they often initiate an insurgency.… (JP 3-24).

It’s striking to read the sheer honesty of this definition since it states the material conditions for insurgencies to emerge. People growing “dissatisfied with the status quo” is certainly putting it mildly, yet one can appreciate, at the very least, the connection made between insurgency and the concrete social conditions that give rise to militant groups that challenge social and political authority, not to mention the control of economic resources. This definition places civilians as central agents of counterinsurgency. What exactly does this entail exactly? Is it referring to the population that should otherwise be involved in insurgency? The discourse civilians believe, uphold, and articulate to others in relation to emerging insurgent groups may either serve to legitimize or delegitimize the latter’s efforts. In terms of discipline, civilians with greater decision-making power in institutions can punish those who lean too far left or who out right support the militant actions taken by a particular insurgency. Beyond mainstream media, the university and academia stand out as one of the most important institutions that legitimize authority and concomitantly justify the State’s actions in suppressing insurrections. The university and academia can certainly be understood as sites of contestation, but they primarily reproduce and actively assist the nation-state’s imperial, colonial, and racial capitalist projects of domination, exploitation, and dispossession.

In Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies, the cultural dimension is described as a key facet of counterinsurgency. If counterinsurgents are detached from the cultural reality of a specific region, they will not be able to ideologically convince a people to oppose an insurrection. Culture, as the document states, “forms the basis of how people interpret, understand, and respond to events and people around them. Cultural understanding is critical because who a society considers to be legitimate will often be determined by culture and norms” (p. 3-1). Indigenous insurgency, on the other hand, will know the local demands and grievances more than a foreign counterinsurgency effort. “The way that a culture influences how people view their world is referred to as their worldview. Many people believe they view their world accurately, in a logical, rational, unbiased way. However, people filter what they see and experience according to their beliefs and worldview. Information and experiences that do not match what they believe to be true about the world are frequently rejected or distorted to fit the way they believe the world should work. More than any other factor, culture informs and influences that worldview. In other words, culture influences perceptions, understandings, and interpretations of events” (ibid). I cite these field manuals at length because it is crucial to know how those in power weaponize the understanding of culture, knowledge, and worldviews to effectively implement a counterinsurgency program, which leads me to discuss the role of the university and academia.

Let’s thus return to Wschebor’s book on the university’s role in supplying imperialism with the knowledge base to reproduce its neocolonial designs in Latin America. The Georgetown Project, as the author notes, prepared a series of systematic studies on counterinsurgency in the region. These studies included “An In-Depth Study of Communist Insurgency in Colombia and the Government’s Response” and “A Study on Insurgency and Counterinsurgency Operations and Techniques in Venezuela, 1960–1964.” Similar studies have been conducted on all continents to “discover” sociological and psychological (ideological) mechanisms that could be weaponized against anticolonial insurgency in the Global South. Means of communication such as the radio and television were without a doubt deployed to indoctrinate people in the liberal and neoliberal ideology.

Unsurprisingly, these studies also targeted urban intellectuals and student movements. Understanding this group’s central role in popular uprisings was of special interest, particularly within the global context of students rebelling against their institutions and the ties these had with capitalist and imperial objectives. Seymour Martin Lipset happened to be one of many sociologists who received funding (75,000 first and nearly 100,000 once he started working for Harvard) to study student movements in Latin America. James Scott also worked for the CIA in some copacity to do research on—i.e., infiltrate—student movements. Margarette Mead and other anthropologists played a similar role in studying Indigenous peoples in colonial and “postcolonial” contexts. Sociological espionage, as Wschebor conceptualizes this imperial academic practice, is particularly crucial for the militarization of the social sciences and the imperial and neocolonial counterinsurgency they serve. After Plan Camelot was cacelled, its central counterinsurgent aims found continuity in other projects, such as ARPA, now known as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Wschebor suggests that all the great empires in the past have “put the symbols and cultural practices of their time at the service of dominating their colonial territories or spheres of influence.” The only difference is that no other empire has deployed the natural and social sciences to such a degree and for as long as it has.

Beyond these research initiatives, the US was involved in systematically restructuring higher education in the region. One of the major goals, as Wschebor writes, were to transform universities into conduits for the transmission of ideologies1 that would facilitate the reproduction of imperial interests and neocolonial designs. The second aim was to eliminate political opposition within Latin American universities, which historically were at the forefront in anti-imperial struggles. The third objective was to strip universities of their autonomy and public character by turning them into enterprises that serve the interests of multinational corporations. Counterinsurgency was common feature of these objectives.

While these studies were being conducted at the behest of empire, particularly its primary counterinsurgent wing of the CIA, radical intellectuals committed to liberation and decolonization were advancing anticolonial and antiimperialist critiques of modernization theory, development, and capitalism. Coincidentally, in 1959 Orlando Fals-Borda and Camilo Torres Restrepo founded the first sociology department in Latin America. Their aim, however, was to situate sociological thought in sites of struggle, distancing itself from the imperial designs impacting universities throughout the region. For those who are aware of this history also know that Orlando Fals-Borda also advanced participatory action research with campesino communities and that Camilo Torres Restrepo was a priest and theologian of liberation who died in combat. These insurgent intellectuals were committed to liberation in both epistemological and material terms. It is within this historical context that a politico-epistemic project emerged in all regions experiencing and resisting colonial and neocolonial forces. Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Claudia Jones, Paulo Freire, Sylvia Wynter, Amilcar Cabral, and Walter Rodney are just a few other thinkers who refused to dissociate thought from praxis.

1 Burton, Orisanmi, in Tip of the Spear, describe in great detail the counterinsurgency of the police: “agents of NYPD’s antisubversive unit, which had infiltrated the Panthers in order to gather intelligence and act as agents provocateurs

1 https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD0430475

Brazil serves as an important case study to consider to understand how research is linked to counterinsurgency. When thinking about counterinsurgency via intellectual colonialism, this is what it looks like: After the 1964 coup in Brazil, the US signed a contract with Brazil to place 51 million books from the US in its universities and to ban radical texts.