…scholars tend to sharpen their pens after the smell of death has dissipated and moral clarity is no longer urgent. —Rabea Eghbariah

I have said it multiple times but it is worth repeating for pedagogical purposes: decolonial thought is not a monolith, nor are its concepts metaphors representing superficial notions of social justice, diversity, equity, and inclusion (Tuck & Yang, 2012). However, decolonial theory’s consumers and critics alike have misrepresented, reduced, and distorted its concepts in ways that have led to their banality. Decolonial thought is either something that is at best an unoriginal version of postcolonial theory, or, at worst, something that is against anticolonial thought and praxis. Both accounts are unequivocally false.

Nonetheless, decolonial thought’s multiple concepts, which are inspired by and born in sites of struggle, have been emptied of their (geo)political and ethical content, as well as praxis orientation. It is imperative therefore to resituate decolonial thought in sites of struggle, which entails seriously thinking, being, and relating within particular places, and acting and walking with others in paths of uncertainty. The historicity of movements and the collective memories refusing to be erased “envisions an ‘unthought known’, imagining and rendering familiar something unfathomable, a conjunction that might have or could have been” (Lowe & Manjapra, 2019, p. 42). The unthought is what Khatibi (1983) referred to as the “silent questions that endure in us” for which we search answers to construct an Other way of knowing (p. 2), remembering, and being. That which could have been a world otherwise (un mundo otro) is what we fight for, what Palestinians and Indigenous peoples everywhere fight for, despite the incredible odds to build a world free of colonial domination, dispossession, and capitalist exploitation. In this article, I interweave personal narratives and reflections with analyses of displacement, dispossession, and colonial domination in the past and present. I argue for the need to think about systems of domination of exploitation as always already entangled historically and geographically. I try to make visible the connections between the settler colonial state of Israel and the crucial role it has played and continues to play in reproducing coloniality not only in Palestine but across the world through the exportation of technologies of colonial violence. Israel can be understood as a central pillar of coloniality (or cornerstone perhaps) and an exemplary case of how various systems and modes of domination and exploitation overlap (settler colonialism, formal/administrative colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, and heteropatriarchy) and are linked to global coloniality. With the systematic destruction of knowledge and history (bombing of schools, universities, libraries, bookstores, and Mosques), displacement and dispossession of millions, and ecological devastation (e.g., cutting of olive trees in the West Bank), we are seeing in real-time the ways in which colonial genocide is accompanied by epistemicide, memoricide, femicide, and ecocide. Israel's colonial project of death reveals the destructive tendency of ethnonationalist states and, most importantly, the imperial designs of a dying Occidentalism that refuses to relinquish power without inflicting incalculable violence on those who find themselves on the receiving end of coloniality.

---

My position as a formerly undocumented immigrant from a campesino village nestled in the southern mountain range bordering Honduras and Nicaragua, who lived in Southern California before “self-deporting” one year after the US-backed coup in Honduras, informs my entangled and relational conceptualization of (de)coloniality. For me, decolonial thought is not simply a theoretical framework informing yet another peer-reviewed but a mode of reading the world from a particular place of understanding, of interrogating systems of power, and, more importantly, of collectively building alternatives to the modern/colonial world.

My village and region, for instance, played a small yet significant role in a much bigger imperialist geopolitical game during the 1980s. The Contras organized on the Honduran side, eventually resulting in my family immigrating to the US. These events reveal how global imperialist forces shape the decisions of everyday people, namely Indigenous, Black, and campesino communities. Like most people, I was not always aware that Israel assisted right-wing authoritarian governments in committing atrocities, including genocide. I was not always aware of the intimate relationship between imperialism, neocolonialism, and Zionism in Latin America. Global coloniality never became so clear until I realized these connections with Latin America can be traced back to the ascendance of the US as a global power after World War II. These connections may seem too abstract when they are not situated in concrete experiences.

The friction between what is seemingly abstract (global) to the very concrete decisions people make at the local level is illustrated through violent displacement and migration. Leaving my village in 1992, after five centuries of (neo)colonial domination, is merely coincidental yet symbolically important in terms of shaping my thinking about the ongoing dispossession, domination, and exploitation of colonized peoples, such as Palestinians, whose fate have been historically overdetermined by various colonial powers. Living in Southern California, experiencing state-sanctioned violence, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts it, and being incarcerated when I was fifteen years old shaped who I am and how I think about the world. These experiences help me understand, albeit slightly, what thousands and millions of children experience under Israeli occupation—children who are kidnapped, tortured, and imprisoned. I include these biographical connections to show how they are conditioned by the historical and social totality in which we participate. Coloniality, therefore, shapes all spheres of social existence and shapes how we see the world and how we position ourselves within it.

Again, decoloniality is not a metaphor, that is, another concept or theory detached from the material social totality of which we form a part. It is a sentipensamiento (feeling-thought), without which I would not be able to comprehend and interrogate the modern/colonial world, its violent institutional arrangements, historicity, and heterogeneity. Without linking thought with emotion, I would be incapable of seeing and feeling the suffering of others who suffer at a distance or who suffer and die alone under the rubble. Eduardo Galeano was probably right when he said that being called an intellectual is one of the most offensive labels he had received since intellectuals tend to act like heads/minds without bodies and emotions.

In this short article, I will not continue to detail my lived experience. Hopefully, through my positionality addressed above, the reader will discern how some of my interpretations are informed by multiple loci of enunciation (or places of understanding) that are linked to the geopolitical order of things where wars, death, and destruction displaced and forced my family to find refuge in the country responsible for our dislocation. Despite the peculiar sensation of being uprooted, many of us continue to keep our eyes (mirada hacia el Sur) toward the many Souths of the world, hoping one day those who cohabit the underside of modernity in all places, will articulate themselves in a struggle against the structural violence that seemingly has no end—a modern/colonial structure that appears natural, fixed, and indestructible.

Why situate decolonial thought in sites of struggle?

I place emphasis on sites of struggle due to my collaboration with the student movement in Honduras, where I learned that the imperial, neoliberal, and neocolonial designs (and their ostensible inevitability, unidirectionality, and naturalization) do not always go as planned when collective action is taken. Student activists taught me that we need to resist recolonizing efforts by collectively creating alternative pedagogical spaces within and beyond the university to organize—spaces where world-making practices, alternative sociabilities, political subjectivities, and alternative ways of knowing may flourish. By “we,” I am referring to those who resist/re-exist and coexist in the underside of modernity—i.e., coloniality. I am referring to those who “have grown up in the suffering that calls for the power of the word and revolt” (Khatibi, 2019, p. 5). The underside of modernity or the undercommons, as Harley and Moten and Haartman also note, is a place in which re-existence and wayward lives refuse to be enclosed/trapped by modernity’s false promises of progress, enlightenment, and salvation. The undercommons are not built on their own: It necessarily depends on radically rethinking everything that has been imposed on us. As Khatibi also notes, “Everything remains to be thought in dialogue with the most radical thoughts and insurgencies that have shaken the West” (p. 2). To think with others aims at establishing an other-thought, one that entails a double critique of Eurocentrism and essentialism in order to eschew returning “to the inertia of the foundations of our being” (p. 2)—a double critique of nonreturn that unsettles the individualist modern subject of “I” and constitutes an-Other way of thinking, being, and relating as a collective “we.” Only by situating decolonial thought in sites of struggle and by centering and building the collective can we begin to unsettle liberalism’s possessive individualism that so easily negates the suffering of others, including when it is undeniably clear that a genocide is taking place (e.g., Palestine, Congo, Tigray).

The “we” that I mention is this act of unsettling that is original and unthought in the face of all tyranny. The thought of this “we” is this historial linking that weaves being and that being weaves—at the margin of metaphysics. We should understand metaphysics as the representation of gods-become-men, the representation of the idea of god embodied in that of man. And in metaphysics, man has always been a “white” man, bearer of the light and its solar concepts. We cannot deserve our life and our death without the mourning of metaphysics. It is this mourning that urges us to pose otherwise the question of the repressed traditions. (Khatibi, 2019, p. 7)

Returning to the banality of (de)coloniality, let us walk slowly since the road is treacherous, serpentine, and long. We can begin by textually tracing the concept but this will only lead to specifying a scholar coining a term, centering once again the all-knowing modern subject whose interiority and genius are solely responsible for naming, representing, and dominating the world. But how about the material conditions of possibility and historicity for certain concepts to emerge and not others? How about modernity’s exteriority (Dussel, 1980; Mignolo, 2000)? That is, how about those who have been systematically excluded by modernity and rendered inferior and nonexistent? How about those who have been portrayed as savage or more recently as “human animals”?

Why, when, and where a concept such as coloniality is enunciated is much more important than who enunciated it. As Segato (2022) observes,

To recognize authorship is not to suggest that there can be ownership when it comes to a critical discourse, as some have thought; instead, it means recognizing the importance and complexity of the historical scene that an author captures and condenses in a singular way in his work. An author is an antenna for his time. To recognize authorship is thus to respect the history that generates thought and occasions the taking of positions in the world (p. 22)

This keen observation unsettles the universality and geopolitics of modern thought whereby the subject speaks from nowhere yet knows all things. Bautista Segalés also notes that we all speak from a particular place (pensar desde). However, this does not mean that one is solely theorizing about one’s place but also theorizing the modern colonial world from that particularity—that is, from historical specificities intimately linked to broader planetary forces. Caribbean scholars have, for instance, made it clear that they were theorizing the world from the Caribbean (e.g., Césaire, Fanon Glissant, James, Wynter) rather than theorizing solely about their locality. Understanding the social totality of the modern/colonial world from an excluded geography of reason is precisely what decolonial thought offers.

All thought is therefore situated, despite Eurocentric claims suggesting otherwise. All thought has material consequences as well. And it is because of what was denied to me through Eurocentric schooling that I came to decolonial theory, which refocused my attention on what modernity has negated for centuries—the exteriority that is nonetheless its constitutive side. As hooks confessed, “I came to theory because I was hurting—the pain within me was so intense that I could not go on living. I came to theory desperate, wanting to comprehend—to grasp what was happening around and within me. Most importantly, I wanted to make the hurt go away”. I came to decolonial theory to comprehend the ongoing displacement resulting from colonial domination and capitalist exploitation Indigenous/campesino and Black communities continue to resist (e.g., Espinosa-Miñoso; Ruth Lozano; Vigoya). I came to decolonial theory to understand the project of death I could not fully comprehend in its entirety but tacitly knew and viscerally felt was a colonial monstrosity that was never truly vanquished after the so-called independence movements in the early 19th century. Decoloniality, once again, has never been a metaphor to me as it is situated in sites of struggle. The Palestinian struggle resisting Zionist settler colonialism, as I address below, demonstrates the urgent need to interrogate Zionism’s intimate linkages to coloniality but also the ways Palestinians are teaching the world how life is affirmed even in the ruins of colonialism.

Zionist Settler Colonialism

Zionist settler colonialism dates back to the 1880s yet it did not gain momentum until the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which created the material conditions for the Nakba and genocide to take place in Palestine today. As Edward Said pointed out, Balfour took “for granted the higher right of a colonial power to dispose of a territory as it saw fit.” Said addressed that “both the British imperialist and the Zionist vision are united in playing down and even canceling out the Arabs in Palestine as somehow secondary and negligible. Both raise the moral importance of the visions very far above the mere presence of natives”.

To better understand Zionist settler colonialism, it is perhaps best to begin with Fayez Sayegh's “Zionist Colonialism in Palestine” (1965) rather than with Wolfe’s or Veracini’s accounts of settler colonialism. According to Sayegh, “The frenzied ‘Scramble for Africa’ of the 1880s stimulated the beginnings of Zionist colonisation in Palestine.” Zionist ideology thus imitated the dehumanizing and racializing ideologies that justified Europe’s and later the US’s colonial projects in the Global South. “By imitating the colonial ventures of the ‘Gentile nations’ among whom Jews lived, the ‘Jewish nation’ could send its own colonists into a piece of Afro-Asian territory, establish a settler-community, and, in due course, set up its own state”.

Although epistemologically linked to Occidentalism/Eurocentrism, Orientalism, and coloniality, Zionist settler colonialism can be considered somewhat different from Europe’s administrative/formal colonial project in Africa and Asia (direct or indirect rule). It is in fact more akin to the United States’ violent and effective dispossession of Indigenous peoples. Like the settlers in the “frontier,” Zionist settlers did not aim to exploit, let alone coexist with, the Indigenous population who had a shared history and collective existence in Palestine.

Despite the differences, World War I set the stage for various imperial/colonial projects to create alliances. In this case, Zionist colonialism and British imperialism established an alliance to enable both the colonization of Palestinian land but also the creation of a Northern imperial outpost in the Middle East that would serve the UK’s geopolitical and economic interests. As Theodor Herzl wrote, "We [Zionists] can be the vanguard of culture against barbarianism” and “antisemites will become our most loyal friends, the antisemites nations will become our allies.” As Herzl admitted, Zionism would help create “an outpost of civilization” in the Middle East. These statements reveal that Zionism is historically, geopolitically, economically, and epistemologically linked to coloniality, understood here as the cornerstone of Western modernity.

From 1917 to the birth of Israel in 1948, Zionists dispossessed and ethnically cleansed Palestinians from their homeland, however incomplete. As Sayegh observed, this imperial/colonial alliance “permitted the Zionist community...to maintain its military establishment (the Haganah). It trained mobile Zionist striking forces (the Palmach), and condoned the existence of ‘underground’ terrorist organisations (the Stern group and the Irgun).”

Although Zionist colonialism in Palestine learned immensely from British imperialism, it looked for an emerging power to complement the support it was gradually losing from the UK. It need a “powerful and more militant supporter to see it through the forthcoming struggle for outright statehood; and the US was...a willing candidate.” It is evident that Zionist settler colonialism has historically maintained an intimate relationship with Euro-American imperialism. But nowhere is this relationship more evident than the unwavering support Israel has received by the West. The West’s refusal to call for a ceasefire or to condemn Israel’s genocide and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians speaks volumes to their shared geopolitical and economic interests in the region.

Racism, Violence, and Territorial Expansion

Structurally, Sayegh describes Zionist colonialism as having three key characteristics: 1) Racism; 2) Violence; 3) Territorial Expansion.

Racism

"Racism isn't an acquired trait of the Zionist settler-state. Nor is it an accidental, passing feature of the Israeli scene. It's congenial, essential and permanent...it's inherent in the very ideology of Zionism and in the basic motivation for Zionist colonisation and statehood….Zionist racial identification produces three corollaries: racial self-segregation, racial exclusiveness and racial supremacy...[which] demands racial purity...the Zionist credo of racial self-segregation necessarily rejects the coexistence of Jews and non-Jews….The Zionist ideal of racial self-segregation demands, with equal imperativeness, the departure of all Jews from the lands of their ‘exile’ and the eviction of all non-Jews from the land of ‘Jewish destination’, namely, Palestine."

Violence

"Since its establishment, the Zionist settler-state has turned its violence both inwardly and outwardly: against the Arabs remaining under its jurisdiction, and against the neighboring Arab states….In the Zionist occupied territories of Palestine, massacres and other outrages visited upon such Arab towns and villages as Iqrith (December, 1951), Al-Tirah (July, 1953), Abu Gosh (September, 1953), Kafr Qasim (October, 1956), and Acre (June, 1965) have been the most infamous"

Territorial Expansion

"No student of the...modus operandi of the Zionist settler-state can fail to realise that Zionist attainments at any given moment...are only temporary stations along the road to ultimate self-fulfillment and not terminal points of the Zionist journey…until 1948, the leaders of Zionism were constantly assuring the world that they harboured no intention of dispossessing or evicting the Arabs of Palestine from their homeland—although evidence abounds they were aiming at nothing less than the...de-Arabisation of Palestine”.

Given the long history of Zionist racism, violent dispossession, and territorial expansion (as well as the miseducation/indoctrination of Israelis), it is not surprising that a recent poll indicated that 86% of Jewish Israelis believe in the Judaization of the Occupied Territories in Palestine or that 87% believed it was justified for the Israeli Occupation Forces to ignore the suffering of Palestinian civilians in Gaza. In one instance, these polls point to Israel’s pedagogy of cruelty that is embedded in the curriculum—a curriculum that dehumanizes Palestinians and justifies further dispossession. In another instance, it reveals that the vast majority support ethnic cleansing and genocide. In surprising contrast, in the US the majority would like for the government to call for a ceasefire, and 70% of young potential voters disapprove of Biden’s policy in Gaza. In the last instance, Israel’s Zionist racial ideology and praxis of domination are diametrically opposed to the global majority that is demanding a ceasefire, an end to the occupation, and decolonization.

(De)Colonial Entanglements and Resistance

Some people (especially liberals) may find it difficult to see and comprehend why a decolonized Palestine is a step toward the liberation of all colonized and dominated peoples. In other words, they may find it difficult to understand how struggles around the world are interconnected. This can be attributed to indifference but it is likely due to a narrow worldview that is unable to comprehend social totality in planetary and relational terms. Liberals are not alone of course since there are even so-called Leftists who seem to only examine things using the nation-state as a unit of analysis or fall into the traps of economic determinism. Decolonial thought, on the other hand, assists in thinking beyond national borders and offers a planetary perspective that makes visible our shared histories and geographies, as well as the ways they are imbricated in one another. It makes visible how the material (political-economic) is always already entangled1 with the symbolic (epistemological, cultural, and spiritual) to configure interconnected systems of domination and exploitation.

An easy way to understand how colonialism(s) are historically and geographically connected is by examining the technologies of violence and control used to maintain the colonial order of things. Settler-colonial states, such as the U.S., Canada, and Israel (to name a few), have developed technologies of violence, management, and control that have made the displacement and repression of Indigenous peoples much more effective and profitable, demonstrating how colonial domination is inseparable from capitalist exploitation. These technologies of colonial violence range from surveillance, military weapons, military training, and torture to population control through reservations, open-air prisons (e.g. Gaza), or concentration camps.

Technologies of colonial violence have historically been used to repress social movements and struggles for liberation and decolonization, most often through death squads, riot police, and prisons. Their function is to maintain the colonial order of things in place. These instrumentalities of colonialism have not only been used internally but have been exported globally. There are too many examples to list; it will suffice to say that authoritarian regimes in “Rhodesia” (Zimbabwe), South Africa, the Dominican Republic, Argentina, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (among others) have received military support and training from Israel to repress social movements and lead genocidal campaigns against Indigenous peoples (e.g., Guatemala2). When the United States is unwilling to tarnish its international reputation, which would otherwise unveil the facade of democracy and “American values,” Israel does the “dirty work” for its imperial sponsor (e.g., when Carter cut off military aid to Guatemala, Israel stepped in).

Settler colonial violence is both internal, whereby Indigenous peoples are violently displaced and/or killed, and external, whereby the technologies of violence perfected in the process of colonizing a territory are tested on Indigenous peoples, which are later advertised as “battle-tested weapons” and exported to other regions. With a violent technological apparatus, Zionist settler colonialism aims to expand territorially while profiting off of the suffering and dispossession of peoples in other lands.

Israel could not have developed these technologies without the assistance of its imperial sponsor: the United States. From 1949 to 2011, the U.S. gave Israel around $115-$123 billion. This financial support enabled Israel to become highly skilled in various areas, such as managing crowds, relocating people by force, conducting surveillance, and carrying out military occupations. As a result, Israel has become a major player in the global industry of repression, where it creates, manufactures, and sells technologies that are utilized by armies and law enforcement agencies worldwide for purposes of control and management of oppressed peoples. Israel has supplied weapons; trained militia, military, and civilian police; developed surveillance technology and repression strategies; and offered various tools for control, ranging from so-called “non-lethal” weapons to border security technology. Some of the border technology and crowd control methods have been used by numerous governments to suppress social movements, as well as deter migrants from leaving and entering countries (e.g., the US-Mexico border).

Resistance: Where there is colonial domination there is also resistance.

The people of Palestine, notwithstanding all its travails and misfortunes, still have undiminished faith in its future. And the people of Palestine know that the pathway to that future is the liberation of its homeland….As a colonial venture which anomalously came to bloom precisely when colonialism was beginning to fade away, it is in fact a challenge to all anti-colonial peoples in Asia and Africa. For in the final analysis, the cause of anti-colonialism and liberation is one and indivisible. —Sayegh

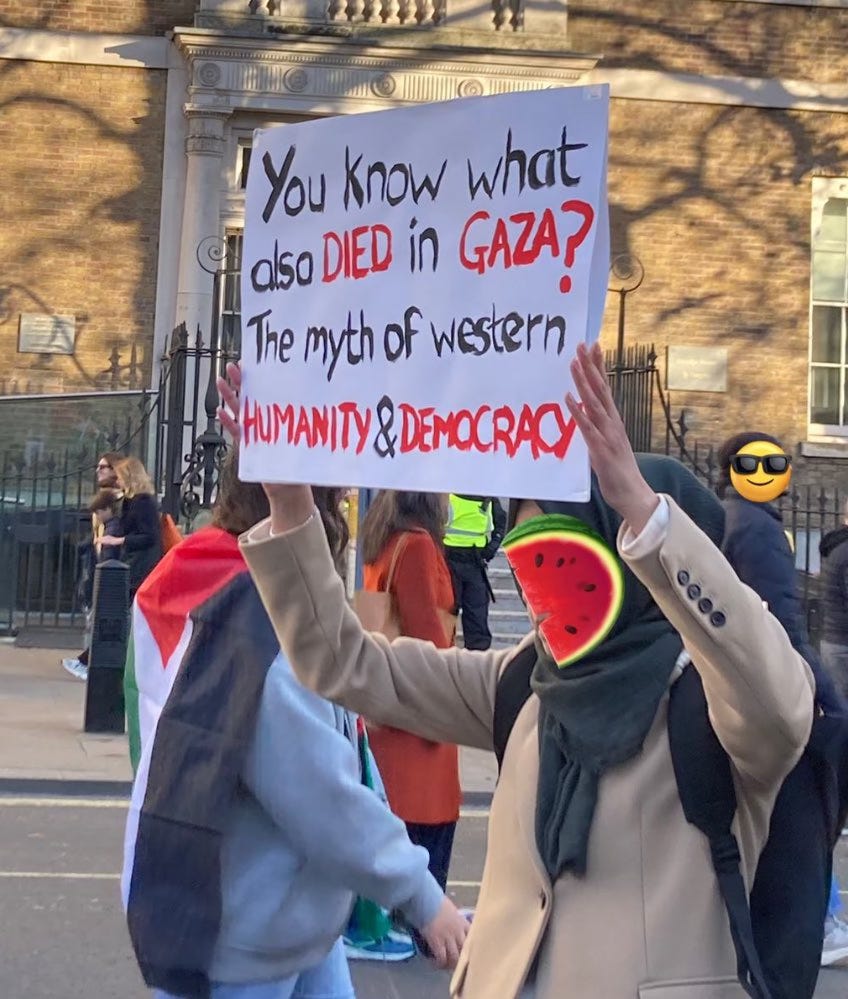

The Palestinian struggle entails a pedagogy of liberation that teaches us about the West’s colonial history, racial ideologies, Zionism, settler colonialism, and collective resistance. It has unmasked the West’s hypocrisy. As Césaire would put it, Palestine has announced to the world that Occidentalism is dying. The world knows it, and the West knows it. And that is why this dying civilization is using the same means that made it the center of the world in the first place: colonial violence, dispossession, and genocide. The world will never be the same after Israel’s genocidal campaign against Palestinians. The West’s complicity and active support of Israel have revealed to the world that its “enlightened” humanity has always depended on the suffering of colonized others. It has always depended on the darker side of coloniality. As a Pro-Palestinian protester carrying a poster illustrated, Western “humanity” and democracy died in Gaza.

Take for instance the dehumanizing and racializing rhetoric used to justify genocide in Palestine (“human animals” or “children of darkness”).

Guatemala: During the civil war in Guatemala, Israel exported military personnel and weapons to the government. Counterinsurgency against Indigenous and campesino communities involved a genocidal campaign similar to the one against Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed and more than a million people were displaced. The period that saw the most destruction and death was precisely when Israel stepped in to help the Guatemalan government systematically raze hundreds of villages. It is estimated that more 100,000 women were raped.

El Salvador: At the same time in El Salvador, death squads were trained for counterinsurgency measures. The estimates indicate that 83% of military imports came from Israel, and that 75,000 people were killed during the civil war.

Honduras: During the U.S.-backed dictatorial regime of Honduras (2009-2022), Israel also gave military support to train the military police. Thousands of people were imprisoned, tortured, and killed.

Nicaragua: In Nicaragua, Israel provided 98% of the arms Anastasio Somoza García used in the last year of his dictatorship, when 50,000 Nicaraguans were killed.

Colombia: In Colombia, Israel didn't only export weapons but also provided counterinsurgency training and intelligence to paramilitary groups. Colombia's largest and deadliest group, Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), was trained by Tel Aviv, which, according to a report from Al Jazeera, "copied the concept of paramilitary forces from the Israelis.” It's for this reason that the current Colombian President Gustavo Petro referred to Yair Klein, a former lieutenant colonel in the Israeli army who established the private mercenary company Spearhead Ltd that trained death squads and right-wing militias in Colombia in the 1980s, in one of his tweets critiquing Israel’s recent actions in Gaza.

Argentina: During the "Dirty War" in Argentina, many Jews were arrested, tortured, and "disappeared." While Jews constituted only 1% of Argentina's population, they made up 12% of the victims. During the Contra Wars in Central America in the 1980s, the "Argentinian model," copied from Israel, was exported to Honduras.

Chile: The Pinochet dictatorship that ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, which committed acts of murder, rape, and torture against its opposition, including trade unionists and socialists, obtained crowd control equipment from Israel, including vehicles equipped with water cannons. Israel also provided surveillance support to the Pinochet regime.