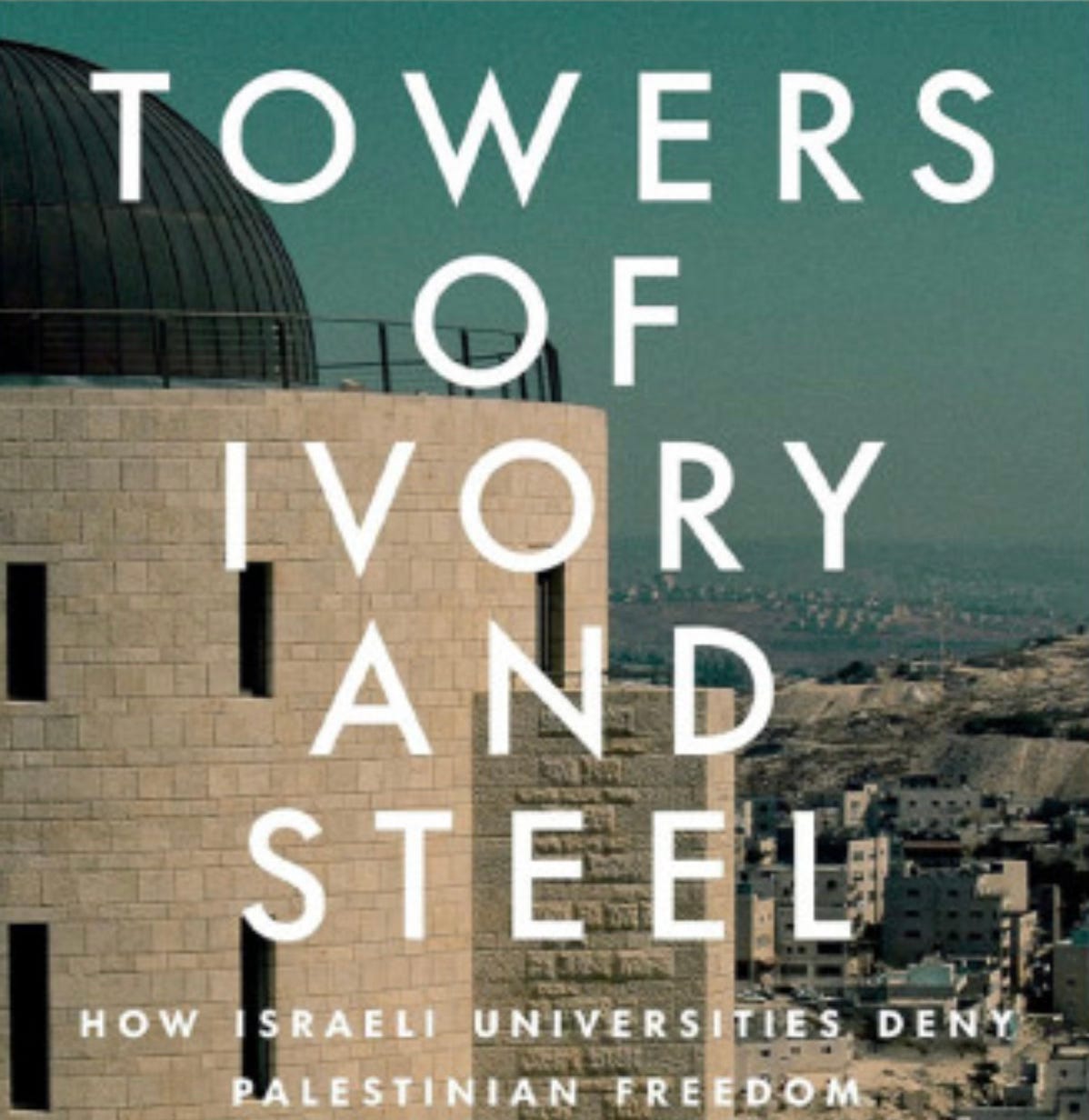

I’m currently re-reading Maya Wind’s Towers of Ivory and Steel, and this book has made me reflect on the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum across disciplines. As I’ve written elsewhere (Fúnez-Flores, 2024), the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum is about the effective control of knowledge, which ‘requires specifically racialized knowledge’ that justifies colonial-racial and patriarchal domination (Gilmore, 2022, pp. 70-71). The coloniality of curriculum can be understood as an imperial/colonial doctrine insofar as it is conceived as a pedagogical mode of imperial domination aimed at colonial domesticity and capitalist exploitation. The dominant curriculum, therefore, seeks to reproduce coloniality in its multifaceted symbolic and material dimensions (race, gender, sexuality, labor, subjectivity, being, knowledge, and power).

The coloniality of curriculum is a pedagogical instrument of control and management. Conceived as such, the colonized will continue to be positioned in the zone of non-being (Maldonado-Torres, 2007), that is, in the dustbin of history (Blaut, 1993), rendered insignificant by the curriculum and thus made nonexistent. The coloniality of curriculum points to racialised affects where the suffering of others does not emotionally move the white ethno-class (Ahmed, 2014; Wynter, 2003; Zembylas, 2021). The inability to feel for others is an integral part of the non-ethical affective economies and racial grammars intimately linked to imperial/colonial projects, domination, exploitation, displacement, and dispossession. The disregard of others is thus constitutive of a modern/colonial structure of feeling.

Maya Wind’s book doesn’t only point to the coloniality of curriculum of archeaology, legal studies, and Middle East studies and the way these disciplines justify settler colonialism, but also makes visible the structural linkages between disciplinary production of knowledge and the concrete dispossession of Palestinians. Knowledge production doesn’t only dwell in the ideological or symbolic as a means to justify domination after the fact. As Wind observes,

the discipline of archaeology constructs evidence to support Israeli land claims through erasure of Arab and Muslim history, and substantiates Israeli use of excavations to expand Jewish settlement and expropriate Palestinian land. Second, legal studies-including ethics law, and criminology-create a discursive and legal infrastructure to justify Israeli violations of international human rights law and the laws of war, continually developing legal interpretations that shield the Israeli state from accountability for its illegal military tactics and permanent military occupation. Third, Middle East studies produces racialized, militarized knowledge about the Middle East that offers a framework to legitimize Israeli violence against Palestinians, and commits regional and linguistic expertise and academic training to the Israeli military and security state. Through their structural ties and collaboration with the Israeli state, these disciplines have themselves become integral sites of knowledge production that maintain, develop, and refine Israel's systems of apartheid and military occupation.

As integral sites of knowledge production that reproduce settler coloniality, these disciplines actively participate in settler colonial violence, dispossession, and ethnic cleansing. One could argue that these disciplines function as technologies of dispossession and not solely as abstract knowledge-producing sites linked to a settler colonial ideology. Certainly, the latter is true but too often the symbolic is overemphasized at the expense of the concrete practices of the ivory tower that directly result in settler colonial dispossession. Archaeology, in this instance, doesn’t only romanticize a biblical past to justify ongoing dispossession. It actively participates in “discovering” archaeological sites that simultaneously erase centuries of Palestinian existence and establish the “research credibility” and rationalizations to displace Palestinians currently living near said sites. It’s not a coincidence that settlements, as Wind notes, are typically established near excavation sites. Despite the violation of the Hague Convention that prohibits occupying power from unilaterally carrying out excavations, Israel currently has 2,600 sites in the West Bank alone. It is evident, therefore, that the “discipline of archaeology…structurally faciliates Israel’s illegal theft of Palestinian artifacts and lands and makes possible their continuous appropriation”.

Colonial, racial, and affective grammars undergird the coloniality of curriculum, where others are invisible wretched beings—nothingness. There is an intimate relationship between the zone of non-being, coloniality, and cartography, which unveils how those dwelling in the zone of nonbeing are conceived as inferior while those in the zone of being of humanity are representative of the white ethnoclass (Wynter, 2003). This modern/colonial cartography is not only sustained through a legal cartography of exclusion (legal studies and national/internation law). It is also fortified epistemologically through education systems entangled with a (material) political economic and legal cartography (education policy), as well as a (symbolic) epistemological cartography or curriculum.

The university is thus a central pillar of settler colonial violence. On the one hand, the curriculum establishes a canon of knowledge that ideologically justifies dispossession and the erasure and systematic destruction of Palestinian knowledge, history, struggles, collective memories, education systems, among other things. This is what is referred to as epistemicide and scholasticide. The coloniality of curriculum hence upholds an epistemology of ignorance (Mill, 1997) that systematically prescribes absence whereby nothing else could exist outside of the Eurocentric canon, narrative, and teleology; no “counter-voice” could be allowed to speak (Wynter, 2003, p. 269). On the other hand, the curriculum produces “administrators, educators, professionals…and other wielders of pen and paper” (Rama, 1996, p. 18) who are directly involved in the dispossession of Palestinians in the present. The university curriculum plays a central role in creating the subjectivities that enable other institutions to run smoothly according to colonial designs and racialized social arrangements. Without the university’s active material and symbolic role in domination, one finds it difficult to conceptualize what settler colonialism in Palestine would look like. What I mean by this is that settler colonialism’s technologies of violence do not appear from nowhere. These technologies, whether archaeological or directly linked to weapons manufacturers, are undeniably produced by universities. It is for this very that any discussion of “decolonizing” the university cannot go without addressing the concrete ways universities participate in settler colonial dispossession and genocide. Otherwise, we risk reproducing what we seek to dismantle.

This reflection on Towers of Ivory and Steel is crucial because it dismantles the illusion that knowledge production is somehow neutral or separate from material structures of power. As you lay out, the coloniality of curriculum is not just ideological—it is infrastructural. It is embedded in the material and symbolic architecture of the university, shaping not only what is known, but who gets to be seen as capable of knowing. The university is not simply a site where settler colonial violence is rationalized—it is a site where that violence is produced.

Maya Wind’s analysis of archaeology, legal studies, and Middle East studies makes visible what decolonial scholars have long argued: that disciplines function as technologies of dispossession. This is key, because too often, critiques of the coloniality of knowledge remain in the realm of epistemology, emphasizing exclusion without fully engaging how academic disciplines actively create the conditions for land theft, militarized violence, and ethnic cleansing. This is more than just a politics of representation—it is about the university as a war machine in the service of settler colonial expansion.

As you point out, this operates not only through content, but through affect and social organization. The coloniality of curriculum shapes who is allowed to feel, who is seen as fully human, and whose suffering registers as an event rather than a background noise to progress. The absence of Palestinian histories and struggles in the dominant canon is not a passive omission; it is an active erasure that facilitates ongoing violence. This connects directly to what Wynter (2003) describes as the modern/colonial cartography of being, where humanity itself is stratified along racial lines, making some lives grievable and others disposable.

One of the most crucial insights here is the necessity of moving beyond “decolonizing the university” as a mere metaphor or curricular intervention. If universities produce the technologies of settler colonialism—whether through archaeological erasures, legal infrastructures of occupation, or direct partnerships with weapons manufacturers—then the struggle must be against the institution itself, not just its content. Decolonization cannot be reduced to inclusion or critique; it must be about dismantling the material and intellectual structures that uphold settler colonial rule.

This also raises questions about the role of trauma in the coloniality of curriculum. If knowledge production is itself a form of slow violence (Nixon, 2011), then universities do not just exclude Indigenous and colonized peoples—they actively inflict intergenerational harm. The production of knowledge is, in many cases, the production of dispossession. This is why the university is not just an “ivory tower” floating above the world; it is an institution that fabricates the very justifications that make genocide and displacement possible.

I appreciate this reflection for refusing to separate the symbolic from the material, for naming epistemicide and scholasticide not as metaphorical concerns but as conditions of real, lived destruction. It forces us to ask: If universities are not restructured to account for their complicity in settler colonial violence, then are we not simply perpetuating the very structures we claim to resist? And if decolonization must go beyond critique, what does it mean to engage in forms of refusal that do not merely seek inclusion within the university, but actively disrupt its ability to reproduce coloniality?

Hi Jairo - Thank your for your research and activism. Could you recommend decolonial scholarship that specifically deals with decolonial management or administration? I am a student, and I dont want to waste time in exploring liberal scholarship that does not center decolonial concerns. Thank you!