The CIA’s Ideological/Psychological Warfare

Counterinsurgency refers to covert actions directed at suppressing dissident, insurgent, and revolutionary actors. Its central objective is to assert control over discourse and communication in order to delegitimize insurgent ideologies and undermine their persuasive appeal among the population that would otherwise serve as an economic base for an insurgency. This involves isolating insurgent groups geographically and socially, neutralizing their tactical advantages in guerrilla warfare, and reinforcing the legitimacy of the State and imperial power. For counterinsurgency efforts to be effective, therefore, the dominant narrative must remain intact insofar as the control of information and communication will shape the configuration of allegiances.

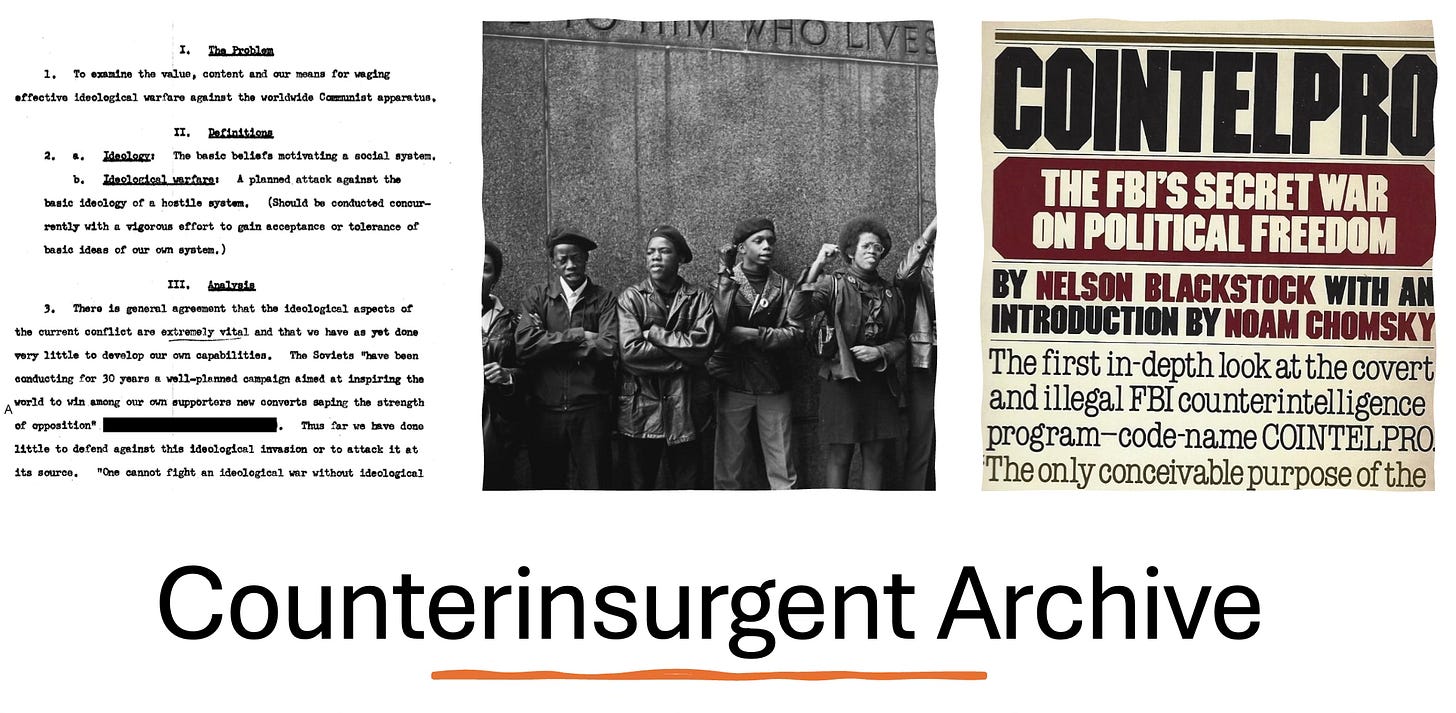

In 1951, the Human Resources Research Institute held a conference on psychological warfare at the Maxwell Air Force base. The Office of the Chief of Psychological Warfare of the Army determined that the Operations Research Office would lead the effort in publishing training manuals on psychological warfare. On April 4, 1952, the CIA wrote “Ideological-Psychological Warfare” (released in 2000), a blueprint for counterinsurgency operations at the national and international levels. The document’s opening line states the problem and objective: “To examine the value, content and our means for waging effective ideological warfare against the worldwide Communist apparatus.” In simple terms, psychological warfare is symbolic warfare insofar as the State depends on the reproduction of a discourse that gives it legitimacy. What stands out in this document, like many official documents of the past, is the honesty in terms of why an ideological warfare is needed in the first place. The document explicitly expresses that “One cannot fight an ideological war without ideological tools” and that “Human activity follows this sequence: emotion, ideas, organization, and action. In our struggle against the Soviets we have organized and acted without developing a positive synthesis of our ideas and without developing ideological shells to disrupt the basic concepts of the enemy.” Cultural bombs, as wa Thiong’o wrote decades later, are as destructive as physical bombs or as I write elsewhere, the canon is a close companion of the cannon.

The State’s symbolic or discursive counterinsurgency should thus support US imperialism’s geopolitical and economic project by attacking communism ideologically, wherever it may appear. Within this document we note the explicit ways theory and knowledge production in general can be used to target communism. The document argues that the US has insufficiently paid attention in “developing ideological shells to disrupt the basic concepts of the enemy” in order to dismantle communism’s theoretical and ideological foundations. It further asserts that communism is greatly informed by theory, whereas US policy takes a more pragmatic approach to solving problems. “It is for this reason, perhaps, that we have overlooked the advantages that can accrue from a well-designed ideological campaign” (p. 2). The CIA hence recognized that physical force alone is not enough for counterinsurgency to be effective when combating an insurgency whose theory and praxis of liberation resonates with a particular population’s demands against the State.

Another salient argument the document makes is that propaganda can only do so much when it’s not tied to a “permanent literature: with a strong history and philosophy.” If counterinsurgency doesn't develop its own “permanent literature,” it will solely rely on physical force, which has proven time and again to be ineffective in the long term. Theory must therefore be developed to capture those who would otherwise support an insurgency. It’s not surprising that the post-world war 2 literature in the social sciences and the humanities developed theories on modernization, development, ethics and social justice (a la Rawlsian), as well as the defanged postmodern and poststructural perspectives that falsely claimed the end of history and master narratives. Anthropological studies that were conducted and published in collaboration with the CIA stand out as one of the most egregious, namely studies that infiltrated student movements and Indigenous communities in (neo)colonial contexts.

Research, as I discuss in more detail in the following section, was key in not only targeting the legitimacy of a particular political philosophy such as Marxism, it also capitalized on the political and ideological rifts emerging from within, aiming to strengthen the most reactionary “communist” forces. As the document states,

“The ideological factor is the Achilles Heel of Bolshevism, a machine put together to impose an ideological pattern that has been demonstrably proven to be inferior. Communism is vulnerable to a counter ideological attack, because whatever moral sanction there is behind the ‘elite’ of Bolshevism, is based on ideology. The more we puncture that ideology and reduce it to cinders in the minds of men, the easier the rest of the job we have set ourselves to do” (p. 6).

It’s evident that top military officials and certainly the CIA have understood the centrality of ideological warfare (e..g, the battle for ideas), noting that military, political, and even economic actions against an insurgency are necessary yet insufficient in reproducing the US’s hegemonic geopolitical position. Non-military ideological warfare is equally important, in other words. For this reason, the university and academia in general, including the broker intellectual class it reproduces, must neatly fall in line with the State’s ideological and material project while presenting themselves as spaces of academic freedom in which inquiry is democratically constituted.

The State certainly rules by wielding its sword but it solidifies its dominion with pen and paper, codified into laws that structure all spheres of social existence, including knowledge producing institutions. In relatively stable socio-political conditions, the State may allow for small pockets of dissidence within the intellectual class in order to maintain the veneer of democracy. This, in turn, establishes legitimacy to what is fundamentally a modern/colonial system of unimaginable violence. When dissident voices become politically unmanageable, however, the State easily recalibrates itself. Its disciplining mechanisms effectively create a culture of fear so that faculty, staff, and students return to their subservient positions, particularly when social movements take on more radical expressions that directly challenge the material and ideological apparatuses of racial capitalism and settler colonialism. Take, for instance, the way faculty, staff, and especially students have been criminalized for speaking out and organizing against genocide. What separates these protests from that of other student-led protests is that the Gaza Solidarity Encampments were not organizing for inclusion or to restructure the curriculum. They undoubtedly achieved this by reclaiming education in the lawns they occupied. But what is of greatest importance to acknowledge is that they examined and amplified the material links between the university’s production of knowledge and the manufacturing of technologies of colonial violence “battle-tested” on Palestinians and exported around the world to repress liberation struggles. It is not surprising that the State’s counterinsurgency on the domestic front is seeking to discursively and materially target students, faculty, and staff whose only crime was to demand for the university to disclose, divest, and delink itself from Israeli weapon manufacturing companies. The counterinsurgent discourse on “pro-Hamas” or “terrorist sympathizers” we see in the mainstream media or the concrete actions such as visa revocations, ICE raids, suspensions, dismissals, and arrests has had a chilling effect, to say the least. The concerted attacks against dissidents reveals, more than anything, that pro-Palestine, anti-genocide, and anti-colonial organizing is perceived as a threat, and that the broker intellectual class in academia or imperial stenographers of mainstream media must continue to play the counterinsurgent role in undermining the legitimate demands of those who have chosen to side with the oppressed. If you are not silent and complicit, there will be consequences.

The CIA’s Ideological/Psychological Warfare Manual, alongside other manuals on counterinsurgency, admits to the ideological strength of insurgency and the centrality of gaining legitimacy via population support at the expense of the State. While counterinsurgency or counterrevolutionary measures have seemingly unlimited resources and military power, the insurgency’s power lies in its philosophy and praxis of liberation (ideology), social and cultural capital, and historical and collective memory that is diametrically opposed to domination. In conventional war, the insurgency would find it impossible to defeat the State’s military, at least in the initial stages of an insurrection. However, in guerrilla and ideological warfare, the insurgency stands a better chance, however long this may take. After all, an insurgency is a protracted struggle that is difficult to anticipate how long it will last until insurgents collectively deliver the final blow against the State. An insurgency’s unpredictability and protractedness are what give it its strength.

In 1953, The Nature of Psychological Warfare was published (released in 2008), and the first line of chapter 1 directly positions the aims in the following way: “Psychological warfare is one of the means nations use to promote their policies and objectives vis-a-vis the outside world” (p. 3). Counterinsurgency in the form of psychological warfare, as the document argues, has been waged since nations have existed, tracing the use of rhetoric and communication theory from ancient to modern times. The Trojan Horse is claimed to be a one of the earliest examples of deception and psychological warfare, though in this instance it is intimately related to physical warfare or direct military action. Unsurprisingly, Nazi Germany is referred to as a contemporary example of the use of psychological warfare via the new technologies designed for mass communication (e.g., radio). Certainly a precursor already existed in the United States with the use of the radio, documentary film, and student and professor exchange programs, and printed publications, but Germany took it to unprecedented levels through the systematic control of information and propaganda, as well as academic and scientific knowledge production.

An important insight that this document provides is the notion that, even when conventional warfare becomes inevitable and when a victor has been declared or “when the shooting war is over”, counterinsurgent action (p. 7), including psychological warfare, must be taken to consolidate the victory. In times of peace or in times of war, counterinsurgency must be used against enemies and friends alike, for it is much more effective to engage in psychological or symbolic warfare before an insurgency begins to employ its own ideological warfare (“the battle of ideas” waged through pen and paper), which, as mentioned above, is much more grounded in the material reality insurgents are trying to radically transform, thus having greater resonance with the general population.

A counterinsurgency’s symbolic or epistemological warfare draws on theoretical advancements of the human sciences, particularly the disciplines and fields that have advanced some form of communication theory. As the text at hand illustrates, “Education, journalism, advertising, public opinion measurement, human relations, labor relations, military morale studies, and community studies have all served as laboratories for developing a body of theory about communication” that serves counterinsurgency (p. 9). Political science, psychology, anthropology, and sociology, as the points out, are one of the most salient disciplines in regards to empirically examining and theorizing communication as integral to social existence. Studies focused on the symbols of communication, mass media’s impact on collective behavior, how recipients of a discourse make meaning of and decisions from the communication available to them, how communities choose or abandon leaders, and, how and why social unrest emerges to threaten the status quo, not to mention the creation of a culture of fear within a (perceived or real) hostile environment.

Means of communication have undoubtedly sought to manufacture consent using the knowledge that comes out of these academic studies. It is not for nothing that the social sciences formed a central role during the Cold War. Education is also listed as yet another important discipline and field of research, namely pedagogy (of domination) and its concomitant theories of learning aimed at indoctrination: “the systematized knowledge of learning and forgetting curves, and of motivations to learn; and the several systematic theories of learning that seek to combine experimental knowledge into a structure of principles” are of great importance for counterinsurgency (p. 9). Whether conveyed through mainstream media, schools, or universities, dominant discourses depend on a counterinsurgent curriculum and pedagogy of cruelty aimed at indoctrination.

Coloniality of Curriculum

As I’ve written elsewhere, the coloniality of curriculum entails the effective control of knowledge, which ‘requires specifically racialized knowledge’ that justifies colonial-racial and patriarchal domination (Gilmore, 2022, pp. 70-71). The reactionary curricular movement unfolding in the US, for instance, is determining what knowledges, languages, histories, and experiences are taught and which ones are systematically silenced. In broad strokes, the coloniality of curriculum is understood as an imperial/colonial doctrine insofar as it is conceived as a pedagogical mode of imperial domination aimed at colonial domesticity and capitalist exploitation. This conceptualization seeks to contribute to understanding the complex ways the dominant curriculum propagates and articulates an imperial/colonial sense of being indifferent toward the suffering of colonized and racialized others, not only within a specific nation-state but also within a planetary frame. The coloniality of curriculum may be deployed to examine how education policies are entangled with broader counterinsurgent tendencies seeking to foreclose the possibility of teaching students about slavery, colonialism, heteropatriarchy, genocide, and other silences of the past (Trouillot, 2015). This does not mean, however, that reactionary curricular movements are the same in all contexts but rather that they adhere to the logic of coloniality whereby the dominant ethnoclass (Wynter, 2003) re-articulates itself as the epistemic, geopolitical, economic, and cultural center, particularly when faced with social uprisings challenging the status quo.

The coloniality of curriculum is a pedagogical instrument of control and management. Conceived as such, the colonized will continue to be positioned in the zone of non-being (Maldonado-Torres, 2007), that is, in the dustbin of history (Blaut, 1993), rendered insignificant by the curriculum and thus made nonexistent. The coloniality of curriculum points to racialized affects where the suffering of others does not emotionally move the white ethno-class (Ahmed, 2014; Wynter, 2003; Zembylas, 2021). The inability to feel for others is an integral part of the non-ethical affective economies and racial grammars intimately linked to imperial/colonial projects, counterinsurgency, domination, exploitation, displacement, and dispossession. The disregard of others is hence constitutive of a modern/colonial structure of feeling.

Pedagogically, the suffering of others is nonexistent or deserved. Colonial, racial, and affective grammars undergird the coloniality of curriculum, where others are invisible wretched beings—nothingness (Baszile, 2019). This abyssal mode of thinking and being, though philosophically and phenomenologically described above, adheres to the logic of coloniality manifested legally through education policy and epistemically through the double movement of modernity, that is, through the constitution of a dominant regime of knowledge or curriculum and the destitution of alternative ways of knowing, being, becoming, relating, feeling, and sensing.

Geopolitics of Curriculum

Drawing on Quijano’s planetary framework and analytic of coloniality, I argue that the coloniality of curriculum is also accompanied by the geopolitics of curriculum, which aligns itself to a spatial or geographic turn in the social sciences (e.g., shifting the geographies of reason). The latter constitutes a geopolitically implicated colonial cartography positioning those dwelling on the other side of the abyssal line or zone of nonbeing as philosophically insignificant Negatively racialized others are designated to manual labor. There is an intimate relationship between the zone of non-being, coloniality, and cartography that unveils how those dwelling in the zone of nonbeing are conceived as inferior while those in the zone of being of humanity are representative of the white ethnoclass (Wynter, 2003). This imperial mode of reasoning entails negating the coevalness or contemporaneity (Fabian, 1983) of those who are systematically made non-existence—that is, those who dwell in colonized, dehumanized, and racialized zones of non-being (Fanon, 1963). This modern/colonial cartography is not only sustained through a legal cartography of exclusion (national and international law). It is also fortified epistemologically through education systems, which are entangled with a (material) political economic and legal cartography (education policy), as well as a (symbolic) epistemological cartography or curriculum, both of which are constitutive of modern/colonial education institutions. When conceived in geopolitical terms, the dominant curriculum reveals how educational experiences within and beyond formal education institutions transcend the nation-state and are implicated in transnational modern/colonial projects and imperial designs.

The geopolitics of curriculum is also entangled with a pedagogy of cruelty that sustains the intersubjective relations regulating and constituting coloniality beyond the nation-state (Segato, 2018). It is undergirded by a powerful colonial rhetoric (counterinsurgency) that simultaneously meets the demands of settler colonial projects and imperial neocolonial designs. The recruitment of students from the Global South who become instrumental in maintaining coloniality is a clear case in point. The Chicago Boys, for instance, nicely illustrate what the geopolitical implications are when neoliberal knowledge or theory is instrumentalized and weaponized as it is put into practice to maintain coloniality through coups and military dictatorships linked to domestic and foreign interests alike. The Schools of the Americas also come to mind, which has trained the most brutal regimes on CIA-approved surveillance, counterinsurgency, and torture techniques.

The pedagogy of cruelty put into practice by the geopolitics of curriculum is hence a complex ensemble of social, pedagogic, and intersubjective relations always already immersed in multiple fields of power. As Gramsci (1999)cogently expressed long ago, ‘hegemony is necessarily an educational relationship and occurs not only within a nation, between the various forces of which the nation is composed, but in the international and world-wide field, between complexes of national and continental civilizations’ (p. 666). In a similar vein, the geopolitics of curriculum is entangled discursively at the global, societal, institutional, and individual levels. It is the dominant discourse—an imperial/colonial counterinsurgent doctrine—that maintains the legitimacy of asymmetrical relations of power.

Many of the changes in higher education can certainly be attributed to neoliberal reforms, yet this is just part of the story. As Stein (2022) critiques, one major shortcoming of higher education research is that it is not frequently historicized within colonial contexts, which leads to the understanding of universities not only as developing linearly and uniformly but also void of historical depth and geopolitical scope. This methodological limitation also prevents one from unsettling the colonial foundations and ongoing violent projects of the university since the “real enemy” is simply the neoliberal restructuring of the university, hence presenting the university as yet another victim rather than an active participant in upholding coloniality. The colonial historiography and the dominant narration of the university continue to silence the past (Trouillot, 2015) while also ignoring the technologies of colonial violence produced by the university in the present (Tabar & Desai, 2016; Turner, 2022). The university not only helps establish a colonial symbolic structure that legitimates physical violence beyond the walls of the ivory tower, but it also actively produces the colonial technologies used to displace Indigenous peoples, such as in Palestine. The recent grant given to Howard University by the secretary of defense seeking to “diversify” national security paints a clear picture of the democratization of domination where students of color in the Global North can also participate in the production of knowledge and technologies of violence used against Indigenous peoples in the Global South. The geopolitics of curriculum gestures toward the analysis and critique of these very real imperial projects in which higher education institutions form an integral part of counterinsurgency in their efforts to silent dissident voices aligned to liberation. By interrogating the historicity, coloniality, and materiality of the university, one can avoid the tendency to critique the university merely as a symbolic or cultural institution (Turner, 2022). The university is responsible for much more when we make more visible and take more seriously its linkages to power and its geopolitical-economic implications within and beyond national boundaries.

Examining the university’s past and present colonial projects uncovers the master narrative upholding the so-called civilizing, modernizing, democratizing, and diversifying mission of higher education. If we take a closer look at distinct higher education models used by previous colonial projects, we find that, although their political, cultural, and economic aims varied, they nonetheless became instrumental to colonial domination and capitalist exploitation. I contend that the university continues to serve as the cornerstone of coloniality and counterinsurgency as it not only legitimates dominant ways of knowing (symbolic structure of psychological warfare) but also actively assists in the production of the material technologies needed to effectively dispossess and dominate colonized peoples. Making the university more inclusive is not what is at stake but rather the need to radically transform, if not dismantle the very colonial foundations of this institution. In other words, diversifying the content (symbolic or curriculum) will not change the geopolitical terms of the conversation (material power) within and beyond the university.

As Stein (2022) suggests, it is necessary to counter the idealization of universities whereby they are conceived as fundamentally good institutions yet increasingly destabilized by neoliberal higher education reforms—victims of rather than complicit in and active participants of domination and exploitation. The colonial foundations are hardly ever addressed when higher education curriculum is only seen through contemporary lenses drawing on critiques of neoliberalism since the 1970s. By historicizing higher education curriculum against the backdrop of colonialism and coloniality, a different picture is painted of its “structural complicity in racial, colonial, and ecological violence” (p. 4). As many have already argued, the geopolitics of curriculum has perpetuated the modern/colonial capitalist world system since the 16th century. Without seriously interrogating the geopolitics of curriculum, it would be difficult to understand, for instance, the effectiveness of Spain’s political, economic, and religious institutions in maintaining the colonial order intact throughout a region as vast as Latin America and the Caribbean. Moreover, it would be difficult to examine the neoliberal economic restructuring of the region without also interrogating the role of the curriculum. Sidelining the geopolitical colonial project of the curriculum would otherwise naturalize colonial domination and capitalist exploitation. In other words, it would erase the dialectical relationship between knowledge and power and the dominant subjectivities reproduced through the counterinsurgent pedagogies of domination constitutive of educational institutions. Understood as a canonizing and homogenizing geopolitical instrument of power, the curriculum thus reproduces the dominant subjectivity necessitated to effectively maintain neocolonial and settler colonial social arrangements.

The university curriculum continues to be complicit in reproducing colonial power and hence is responsible for sustaining asymmetrical social relations of power. Its aim is the systematic canonization of knowledge and thus the erasure of Indigenous systems of knowledge, images of the world, collective memories, and insurgents ways of thinking of doing. The coloniality of curriculum upholds an epistemology of ignorance (Mill, 1997) that systematically prescribes absence whereby nothing else could exist outside of the Eurocentric canon, narrative, and teleology; no “counter-voice” could be allowed to speak (Wynter, 2003, p. 269). Only the colonizer is permitted to speak on behalf of the colonized.

The curriculum continues to produce “administrators, educators, professionals,…and other wielders of pen and paper” (Rama, 1996, p. 18). Neocolonialism in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as in other continents, is contingent upon learned individuals, usually from the dominant ethnoclass but also from the counterinsurgents within our own communities, who effectively wield their power from the lettered cities (universities) of the region. The university curriculum plays a central role in creating the subjectivities that would enable other institutions to run smoothly according to colonial designs and racialized social arrangements. Without the complicity of the university and its geopolitically implicated curriculum and pedagogy of cruelty, the domination of a region as vast as Latin America and the Caribbean would be inconceivable. Therefore, the curriculum is intimately linked to the geopolitical economic project of modernity/coloniality, and it positions the Eurocentric subject as the only subject worthy of speaking, thinking, knowing, and existing. Other histories, knowledges, and experiences are ontologically insignificant, and thus should be erased through genocidal and scholasticidal means (I’ll discuss scholasticide in more detail in another post).