Aníbal Quijano: (Dis)Entangling the Geopolitics and Coloniality of Curriculum

Sections from forthcoming article (The Curriculum Journal)

Introduction

The power of concepts cannot be underestimated insofar as they simultaneously enable us to interrogate the world and take action to unsettle colonial, racist, capitalist, and heteropatriarchal structures. Theories and concepts can either serve as behavior-regulating discursive systems (Wynter, 2003) that maintain the modern/colonial order of things or they can serve as catalysts for collective action seeking to dismantle said order. When concepts are imposed on others, however, they have the pedagogical ability to distort the understanding of social reality, justify material dispossession, domination, and exploitation, and prevent collective action. On the other hand, when concepts emerge within sites of struggle, they find their theoretical validity in their praxis orientation toward radical social transformation. González Casanova (1987) claims that it is impossible to wage a collective struggle without concepts, that is, without conceptual tools to read, interrogate, and comprehend the world in which our actions unfold. Take, for instance, decolonial theories and their concomitant concepts, which are not problematic in and of themselves, as some critics like to claim, but are rather problematic when concepts are abstracted from the material contexts from which they emerge. In other words, when the symbolic (cultural) is underscored over the material (political-economic) and when both are underscored as ontologically separate domains, this tends to obfuscate how they are entangled in everyday practices.

In this essay, I thus explore the intersections of coloniality, curriculum, and the geopolitics of knowledge to make the symbolic/discursive and material linkages of coloniality more evident. Coloniality refers to the discourses and practices that reproduce racial-colonial, hetero-patriarchal, and capitalist relations of power and institutions (political, economic, symbolic, cultural, and social institutions). As an analytic, coloniality assists in critically interrogating how categories, theoretical perspectives, and regimes of knowledge reproduce domination and exploitation. More broadly, decolonial theory assists in examining social practices and discourses that form part of all spheres of social existence, including education institutions and their Eurocentric curriculum and pedagogy rooted in the logic of coloniality. Curriculum is undoubtedly central to this discussion, particularly when reconceptualised vis à vis epistemological debates centered on Eurocentrism and the geopolitics of knowledge critiqued by decolonial discourses[i].

Despite the widespread use of the concept of coloniality across various fields of research, there is a lack of sustained engagement with Aníbal Quijano’s untranslated publications. It is worth noting that, initially, Quijano’s (1991/2007) concept of coloniality of power was not widely cited in anglophone contexts, with the exception of Latin American and Caribbean scholars working in the Global North (Grosfoguel, 2007; Maldonado-Torres, 2007; Mignolo, 2000; Wynter, 2003). In educational research, the first peer-reviewed articles to use the concept of coloniality outside of the modernity/coloniality group (e.g., Walsh, 1998) was published in 2004 (Carter, 2004), but without any reference to Quijano’s work or clear description of the concept of coloniality. This means there was a gap of thirteen years during which education scholars in anglophone contexts did not refer to the concept of coloniality. Not long after, a more serious engagement is taken up by Nathalia Jaramillo and Peter McLaren (2006, 2008, 2010), Vanessa Andreotti (2011), Noah de Lissovoy (2010), and Joao Paraskeva[ii] (2011). It is not surprising that they were the first to draw on decolonial theory in general and Quijano’s work in particular since they were already in dialogue with the knowledge production from the Global South, which took a radical decolonial theoretical turn to shift the geographies of reason within the broad field of education research (Gordon, 2011). These publications did not only refer to coloniality symbolically or epistemically but, more importantly, addressed it as intimately linked to material relations of power, racial social classification, and gendered/sexual modes of domination.

Quijano’s conceptualization of coloniality of power has undoubtedly influenced a wide range of disciplines, including sociology (Bhambra, 2014; Grosfoguel, 2007; Patel, 2017), philosophy (Castro-Gómez & Grosfoguel, 2007; Gandarilla Salgado et al., 2021), anthropology (Bonilla, 2020; Restrepo & Escobar, 2005), history and historiography (Lowe, 2015), literary and cultural studies (Escobar, 2007; Pratt, 2022), geography and political ecology (Sultana, 2022), and education (see, e.g., the literature review by Shahjahan et al., (2022)). The concept of coloniality of power entangles the material (political-economic, ontological, and existential) with the symbolic (social, cultural, and epistemic). However, education scholarship drawing on and contributing to decolonial thought does not always make these connections explicit. Some education scholars place greater emphasis on the epistemological or symbolic/cultural (e.g., Carter, 2008), while others underscore social ontology and the material relations of power (Monzo & McLaren, 2014). On the other hand, geopolitically attuned perspectives informing comparative and international education (Andreotti et al., 2016; Fúnez-Flores, 2022b; Fúnez-Flores et al. 2022c; Shahjahan, 2016; Stein, 2021) emphasise both the material and symbolic more explicitly, utilising the geopolitics of knowledge as an analytic to address how the curriculum is instrumentalised through the internationalisation of higher education supported by international financial organisations and universities.

Situating and theorising the curriculum geopolitically provides a valuable way out of the analytical and theoretical dead-end in which many curriculum theorists in the United States buried themselves when conceptualizing, framing, and thus confining curriculum solely as a national concern, which Pinar (2006) and Paraskeva (2016) admonished us to avoid while also maintaining a critical view toward the so-called internationalization of curriculum studies. I seek to avoid the methodological nationalism (and methodological individualism) characteristic of education research in general and curriculum studies, in particular, to modestly contribute to the transnational perspectives emerging from decolonial studies of education and curriculum studies (Bhambra et al., 2018; Grosfoguel et al., 2016; Jupp et al., 2020; Paraskeva, 2016). The dominant curriculum, as I explicate later, has always been intertwined globally and utilized as a technology of control and management. Reconceptualising neoliberal globalisation as global coloniality, in this case, unveils the intimate linkages of power and global circuits of knowledge production, especially when considering how the dominant curriculum is restructured to align with capitalist interests hiding under seemingly harmless terms (e.g., global competence, global knowledge economy, and internationalization of curriculum).

In curriculum studies, the emerging scholarship drawing on decolonial theory usually does not maintain a sustained dialogue with Quijano’s work (which begins in the 1960s), with the exception of those who adopt materialist perspectives (e.g., Fúnez-Flores, 2023; Díaz Beltrán, 2018; Leonardo & Porter, 2010; Jaramillo & McLaren, 2008; Paraskeva, 2016; Rose, 2019; Streck & Adams, 2012). Despite having articulated decolonial theory’s primary analytical concept, which has informed the social sciences and humanities for the past three decades, Quijano’s work surprisingly remains marginal in the broad field of education and curriculum studies[iii]. One can even observe how Global North scholars building upon his work in other disciplines tend to limit their attention to two of his publications (Quijano, 1991/2007, 2000). Although the use of coloniality of power is being deployed by some scholars, Mignolo’s (2000, 2010) epistemological or symbolic emphasis on coloniality of knowledge tends to dominate the discussion. The issue does not lie in Mignolo’s articulation of coloniality, since his work is greatly informed by Quijano, but rather in the way it has been consumed and adopted by education scholars interested more in epistemological or cultural concerns. The overemphasis on the epistemological, without a material base and serious ontological considerations, tends to obfuscate the geopolitical implications and entanglement of colonialism, heteropatriarchy (Jivraj et al., 2020), and racial capitalism,

Given the limited engagement with Quijano’s work, in the following section, I review untranslated publications to point to the distinct ways he conceptualised coloniality. I also sketch out his understanding of the modern/colonial world as a heterogeneously configured and always already contested social-historical totality, a conceptualisation worth seriously thinking about (and with) since it points to a dynamic social ontology in which conflict, resistance, and re-existence become constitutive parts of decoloniality. Despite the homogenizing and racializing logic of the modern/colonial state, everyday social practices point to alternatives. When alternative ways of knowing persist despite dominant discourses saturating the interpretation of the world, decoloniality becomes more visible in terms of its geopolitical and ethical implications. In some ways, Quijano’s conceptualisation of a heterogeneous totality parallels Glissant’s (1997) conception of totality as an ‘entanglement of world-wide relation’ of alterities pointing to the existing alternatives created within a modern/colonial world that appears naturally fixed and unchangeable. Subsequently, I sketch out the contours of the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum. Although this article is primarily conceptual, I do offer a few empirical cases to illustrate how the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum are expressed in various contexts. I focus on coloniality’s broader geographic scope and temporal depth, which I argue allows for a more complex interrogation, critique, and interpretation of curricular discourses and pedagogical practices within and beyond educational institutions. In thinking of curriculum and pedagogy more broadly, I situate this article within the post-re-conceptualist curriculum movement (Malewski, 2005) advancing a multiplicity of critiques of curriculum and colonialism from systematically silenced perspectives, geographies, and histories (Jaramillo, 2012, McLaren & Jaramillo, 2005, 2008). The geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum, as I explicate in more detail throughout this essay, departs from nation-state perspectives by advancing broader analytical frames and planetary perspectives that unveil the intimate relationship between symbolic and material domination.

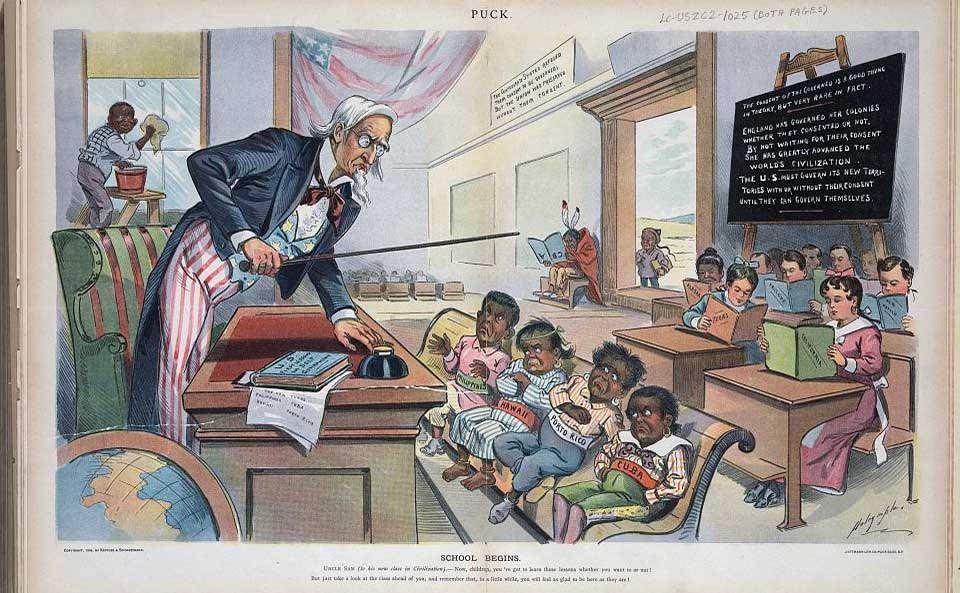

School Begins: From Puck Magazine

Review of Quijano’s Contribution to Social Theory

Quijano’s body of work contributed in original ways to dependency theory and theories of internal colonialism in the 1960s and 1970s; debates on historiography, modernity, culture, and identity in the 1980s; and decolonial theory with his conceptualisation of the coloniality of power from the early 1990s to 2018. His scholarship is perhaps best conceptualised in three phases, all of which revolve around the broad concept of dependency. Quijano’s work shifted from political-economic considerations of dependency to more entangled materialist and symbolic analyses and interpretations of modernity and coloniality. The latter conceptualization informs the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum when interrogating how knowledge and power are articulated across various scales to reproduce material and symbolic dependency. To limit the scope of this review, I will only discuss Quijano’s second and third intellectual phases.

Modernity, Colonialism, and Materialist Theory of History (1980s)

As early as the 1980s, Quijano (1981, 1988, 1989a, 1989b) entered his second intellectual phase, where he shifted his materialist political-economic analyses and interpretations of dependency to more symbolic, cultural, and epistemic issues related to modernity, colonialism, and knowledge production. Although Quijano had an emerging critique of Eurocentric thought between the 1960s and 1970s, it became more explicit in the 1980s, namely with the publication of Sociedad y Sociología [Society and Sociology]. In this piece, he described the paradoxical consequences of French structural thought in defeating and invalidating the original advances made by dependency theory. While dependency theory successfully countered modernisation theory in the first couple of decades after World War II, it paradoxically failed with the advancements of structural Marxism. Eurocentric Marxist perspectives successfully replaced endogenous knowledge production from Latin America and the Caribbean, including ‘Third World’ Marxist interpretations of colonial and postcolonial contexts. Eurocentric categories thus re-established themselves as the most valid conceptual tools for interpreting the periphery’s political-economic and socio-cultural reality.

Structural analyses placed little value on investigations centered on concrete social change and systematically ignored everyday sociocultural existence and resistance, which prevented the analysis of the historical-structural heterogeneity of Latin America and the Caribbean. As Segato (2011) observes, this region’s heterogeneity does not merely consist of the coexistence of “diverse temporalities, histories and cosmologies” (p. 25) but also multiple social relations of production, including non-capitalist modes of production, such as reciprocity and Indigenous communalism. Therefore, ignoring the existence of political-economic and sociocultural heterogeneity disavows the endogenous knowledge production rooted in the realities, histories, and struggles of the region.

Quijano (1981) raised a salient question about the relationship between dominant schools of thought based on historical materialism and radical thought in Latin America and the Caribbean. He questioned whether the latter was always-already a situated materialist social theory and praxis embodied by intellectuals and communities of resistance, or if it necessarily had to be foundationally constituted by the former. Quijano argued that applying historical materialism dogmatically hindered social transformation by displacing historically and geopolitically situated thought and praxis. Dominant understandings of historical materialism hence led to univocal analyses and interpretations. As Quijano (1981) stated, when adopted mimetically, historical materialism ‘was really a catastrophe…for the formation of theoretical and political thought. This rampant ideology, which was absolutely useless…emptied the categories, proposals, and questions of real content’ (p. 165, my translation).

In the late 1980s, Quijano’s analyses of modernity and Eurocentric rationality approximated what he would conceptualise as coloniality in 1991. He emphasized the need to advance new problematics, questions, concepts, and paradigms that would enable the critical reading, interpretation, and comprehension of the neoliberal reconfiguration of the modern/colonial world. Quijano’s prescient thought challenged Eurocentric assumptions and pointed to the urgent need to advance alternative theories. As he stated:

Perhaps one of the interesting things in Latin America is that of the possible emergence of a new problematic. In a way, culture begins to be de-Europeanised; all the myths of Eurocentric origin begin to disintegrate. And everything that this mythology built at the level of paradigm, of the theory of social classes and its form of knowledge, is disintegrating. What remains of it will be the founding nucleus of the problematic that emerges from now on. (Quijano, 1988, p. 169, my translation).

Quijano urged us to question Eurocentric thought paradigmatically, including its theoretical and methodological commitments. This categorical imperative calls for advancing concepts that can unsettle Eurocentric social theory and respond to the geopolitical task of dismantling material and symbolic structures of power shaping the reality of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Symbolic and Material Entanglement of Coloniality of Power

To understand Quijano’s third intellectual phase, it is important to reference a paper presentation he gave at the International Colloquium on Interdisciplinarity organised by UNESCO in Paris (April 1991). Quijano addressed the crisis of modernity in epistemological/symbolic and ontological/material terms, putting into question ‘the foundations of the universalist aim of Western rationality’ (p. 354, my translation). He argued that modernity’s crisis is a result of its cognitive model, which is linked to capitalist relations of power and ontological or metaphysical ambitions to reach universality. These critiques resonated with Dussel’s (1980) earlier geopolitical and ethical concerns with modernity’s exteriority, that is, the systematically excluded, dominated, and exploited geographies and peoples. Universalist ambitions have resulted in the ontological/existential and epistemological/symbolic negation of those on the receiving end of capitalist modernity and colonialism. Therefore, seriously thinking with those who have been systematically excluded and rendered inferior by modern/colonial discourses and practices becomes an ethical imperative. Quijano also called for the decolonisation of social, cultural, and political-economic relations and the epistemological reconstitution founded upon intercultural communication and exchange. Here, decolonial theory’s curricular and educational implications become more explicit, as it points to the bankruptcy of what can be referred to as the coloniser’s curriculum model of the world—a modern epistemological model that cannot offer solutions to the many problems it has created. These conceptualizations anticipate what Quijano would later refer to as the coloniality of power.

Coloniality of Power. Quijano (2000b) provides one of the most complex descriptions of coloniality in an untranslated text. Coloniality is understood as “one of the constitutive and specific elements of the global matrix of capitalist power. It is founded on the imposition of a racial/ethnic classification of the world’s population, serving as the cornerstone of such power. It operates on every material and subjective plane, sphere, and dimension of everyday social existence” (p. 342, my translation). As one can observe, coloniality is conceptualized in heterogeneous terms, illustrating its multidimensional and planetary scope. The category of race also functions as a modern/colonial technology of control and management. It serves as an axis around which other structures of domination and exploitation revolve, including the racialization of knowledge production for which education institutions are responsible. This heterogeneous colonial-racial-capitalist matrix of domination is constituted by the systematic control of labour, sex, gender, sexuality, subjectivity, education, authority, and nature. Interconnected, interdependent, and co-constitutive structures of domination and exploitation are not only nationally configured but are also always-already entangled historical processes and geopolitical frictions (Lowe, 2015) articulated globally by Eurocentric political, economic, social, and cultural institutions (e.g., racial capitalism, heteropatriarchy, Eurocentric rationality, education systems, and liberal democracy). The geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum, as I describe below, demonstrate how knowledge is used as yet another geopolitical instrument deployed to justify and maintain the coloniality of power.

Pedagogically, it is best to conceive of coloniality in relational terms, always already entangled materially and symbolically. It is conceptually and analytically useful to refer to the coloniality of power relations, coloniality of knowledge relations, coloniality of gendered/sexual relations, coloniality of nature relations, coloniality of political-economic relations, and the coloniality of intersubjective relations. Referring to these analytical concepts’ relational dimensions and varying subject positions situate them ethically and geopolitically within multiple fields of power and spheres of social existence. However, it is important to note that coloniality is configured distinctly across space and time due to the historical specificity of colonialism in any particular region. By understanding the coloniality of power as intersubjective and relational, we can examine how colonial relations of power are contested by the heterogeneous realities, histories, knowledges, struggles, experiences, and modes of coexistence. Focusing on the irreducibility of historical-structural heterogeneity and its epistemological and geopolitical possibilities enables the articulation of decolonial thought and praxis in distinct contexts, particularly in rethinking, resisting, and transcending the longue durée of coloniality (Author, 2022c). Quijano’s attention to heterogeneity allowed him to shift his attention toward decoloniality, which amplifies the multiplicity of ways of thinking, being, co-existing, sensing, doing, and relating that resist the matrix of coloniality while simultaneously creating the conditions for escaping the seductive existential-epistemological prison of modernity (Sibai, 2016)

Geopolitics and Coloniality of Curriculum as a Planetary Frame of Reference

I will now discuss curriculum in more detail, following Quijano’s examination of heterogeneously configured contexts through geopolitically attuned analytical concepts. Decolonial theory’s planetary frame of reference or broader geographic scope and temporal depth enable one to situate reactionary curriculum movements within global re-Westernisation projects (Mignolo, 2021). In the US, reactionary discourses and policies aim to discredit critical race theory (CRT) and shape public opinion on education, curriculum, and pedagogy. The consequences are more severe than the discreditation of CRT since what is at stake is the restructuring and realignment of the curriculum according to the logic of coloniality. CRT becomes the justification, while the outcome is the systematic erasure of historically excluded experiences and knowledges, as well as their resistance to colonialism, racism, capitalism, slavery, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and genocide, and a recommitment to whiteness and Eurocentrism. Quijano’s broader analytical lens of coloniality sheds light on the underlying logic informing the restructuring of curriculum.

Heavily drawing on Quijano’s work, Mignolo (2021) reveals that reactionary re-Westernisation projects aim to silence counter-narratives that carry the potential to unsettle coloniality. Since counter-narratives are perceived as threats, it is unsurprising that we are seeing systematic attacks against CRT, ethnic studies, and decolonial theory. These concerted attacks are evidenced by the discourses expressed by mainstream media, politicians, and comprador intelligentsia. After all, the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum are about the effective control of knowledge, which ‘requires specifically racialized knowledge’ that justifies colonial-racial and patriarchal domination (Gilmore, 2022, pp. 70-71). The reactionary curricular movement unfolding in the US, for instance, is determining what knowledges, languages, histories, and experiences are taught and which ones are systematically silenced. A specific and recent case in point is the banning of the Advanced Placement course in African American Studies by Ron DeSantis, Florida’s governor (Clayton, 2023). The small gains made in the curriculum through previous struggles (e.g., student movements in the 60s fighting for ethnic studies programs) are being lost on various fronts, varying from parent associations to media propaganda to education bills, the latter of which seeks to exclude knowledge that questions the whiteness, epistemic authority, and official history of the State.

At the heart of the reactionary discourses restructuring the curriculum, we find colonial, white supremacist, heteropatriarchal, and racist pedagogies aimed at silencing counter-discourses and domesticating Others and dominant groups alike, rewarding the latter to a great extent, persuading and coercing the former, and punishing those who refuse and actively resist coloniality. Education bills have been passed into law (Sachs, 2022). Books and ethnic studies programs have been banned[i], thus transforming reactionary discourses into a concrete reality where feminist, LQBTQ+, Latinx, Asian, Black, and Indigenous voices are further silenced. To unsettle these discourses and practices, the concept of the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum, as I explicate below, can be employed to understand local reactionary curriculum movements as well as curriculum reform within the broader context of neoliberal globalization. I thus separate the concepts of coloniality of curriculum and geopolitics of curriculum to reveal this analytical distinction.

Coloniality of Curriculum (United States)

In broad strokes, the coloniality of curriculum is understood as an imperial/colonial doctrine insofar as it is conceived as a pedagogical mode of imperial domination aimed at colonial domesticity and capitalist exploitation. This conceptualisation seeks to contribute to understanding the complex ways the dominant curriculum propagates and articulates an imperial/colonial sense of being indifferent toward the suffering of colonised and racialised others (Fúnez-Flores, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c), not only within a specific nation-state but also within a planetary frame. Although this article is not empirical per se, as an analytic, the coloniality of curriculum may be deployed to examine how education policies are entangled with broader global tendencies seeking to foreclose the possibility of teaching students about slavery, colonialism, heteropatriarchy, genocide, and other silences of the past (Trouillot, 2015). The dominant curriculum, therefore, seeks to strengthen coloniality in its various dimensions (gender, sexuality, subjectivity, being, knowledge, and power). This does not mean, however, that reactionary curricular movements are the same in all contexts but rather that they adhere to the logic of coloniality whereby the dominant ethnoclass (Wynter, 2003) re-articulates itself as the epistemic, geopolitical, economic, and cultural center, particularly when faced with social upheaval (e.g., whitelash).

Within the increasingly polarized sociopolitical context of the US, attacks against curriculum have become more systematic and coordinated. Since January 2021, thirty-three states have introduced or pre-filed educational gag orders (Sachs, 2022). Of the 137 bills introduced, eighty-seven are from the year 2022 alone (Gross, 2022), and eighty-eight of the bills are currently live (Sachs, 2022) and “target k-12 schools,...higher education,...and include a mandatory punishment for those found in violation” (Sachs, 2022). Some of the bills even allow parents, students, or a random citizen to sue the school district if they feel that the teacher or district is in violation of these laws. This has resulted in an architecture of surveillance that seeks to create a school culture of fear while also disciplining teachers as the workers that they are. This new apparatus, more importantly, renders students’ lived experiences, histories, languages, and struggles insignificant.

The coloniality of curriculum is a pedagogical instrument of control and management. Conceived as such, the colonised will continue to be positioned in the zone of non-being (Maldonado-Torres, 2007), that is, in the dustbin of history (Blaut, 1993), rendered insignificant by the curriculum and thus made nonexistent. The coloniality of curriculum points to racialised affects where the suffering of others does not emotionally move the white ethno-class (Ahmed, 2014; Wynter, 2003; Zembylas, 2021). The inability to feel for others is an integral part of the non-ethical affective economies and racial grammars intimately linked to imperial/colonial projects, domination, exploitation, displacement, and dispossession. The disregard of others is hence constitutive of a modern/colonial structure of feeling.

Pedagogically, the suffering of others is nonexistent or deserved. Colonial, racial, and affective grammars undergird the coloniality of curriculum, where others are invisible wretched beings—nothingness (Baszile, 2019). With the ongoing critiques of CRT, gender studies, and ethnic studies, students are taught that their histories and struggles are unworthy, that certain books are mere distortions of reality, and that their identities are perversions to the white cis-hetero norm. This abyssal mode of thinking and being, though philosophically and phenomenologically described above, adheres to the logic of coloniality manifested legally through education policy and epistemically through the double movement of modernity, that is, through the constitution of a dominant regime of knowledge or curriculum and the destitution of alternative ways of knowing, being, becoming, relating, feeling, and sensing.

Geopolitics of Curriculum (Latin America and the Caribbean)

Drawing on Quijano’s planetary framework and analytic of coloniality, I argue that the coloniality of curriculum is also accompanied by the geopolitics of curriculum, which aligns itself to a spatial or geographic turn in the social sciences (e.g., shifting the geographies of reason). The latter constitutes a geopolitically implicated colonial cartography positioning those dwelling on the other side of the abyssal line or zone of nonbeing as philosophically insignificant Negatively racialized others are designated to manual labor. There is an intimate relationship between the zone of non-being, coloniality, and cartography that unveils how those dwelling in the zone of nonbeing are conceived as inferior while those in the zone of being of humanity are representative of the white ethnoclass (Wynter, 2003). This imperial mode of reasoning entails negating the coevalness or contemporaneity (Fabian, 1983) of those who are systematically made non-existence—that is, those who dwell in colonised, dehumanised, and racialised zones of non-being (Fanon, 1963). This modern/colonial cartography is not only sustained through a legal cartography of exclusion (national and international law). It is also fortified epistemologically through education systems, which are entangled with a (material) political economic and legal cartography (education policy), as well as a (symbolic) epistemological cartography or curriculum, both of which are constitutive of modern/colonial education institutions. When conceived in geopolitical terms, the dominant curriculum reveals how educational experiences within and beyond formal education institutions transcend the nation-state and are implicated in transnational modern/colonial projects and imperial designs.

The geopolitics of curriculum is also entangled with a pedagogy of cruelty that sustains the intersubjective relations regulating and constituting coloniality beyond the nation-state (Segato, 2018). It is undergirded by a powerful colonial rhetoric that simultaneously meets the demands of settler colonial projects and imperial neocolonial designs. The recruitment of students from the Global South who become instrumental in maintaining coloniality is a clear case in point. The Chicago Boys, for instance, nicely illustrate what the geopolitical implications are when neoliberal knowledge or theory is instrumentalized and weaponized as it is put into practice to maintain coloniality through coups and military dictatorships linked to domestic and foreign interests alike.

The pedagogy of cruelty put into practice by the geopolitics of curriculum is hence a complex ensemble of social, pedagogic, and intersubjective relations always already immersed in multiple fields of power. As Gramsci (1999)cogently expressed long ago, ‘hegemony is necessarily an educational relationship and occurs not only within a nation, between the various forces of which the nation is composed, but in the international and world-wide field, between complexes of national and continental civilizations’ (p. 666). In a similar vein, the geopolitics of curriculum is entangled discursively at the global, societal, institutional, and individual levels. It is the dominant discourse—an imperial/colonial doctrine—that maintains its hegemonic position through neoliberal higher education institutions, as well as through the pedagogical discourses and social practices they legitimate. It is critically urgent to historicize education institutions in order to unsettle their colonial foundations.

As Stein (2022) critiques, one major shortcoming of higher education research is that it is not frequently historicized within colonial contexts, which leads to the understanding of universities not only as developing linearly and uniformly but also void of contextual and geopolitical considerations. This methodological limitation also prevents one from unsettling the colonial foundations and ongoing violent projects of the university since the “real enemy” is simply the neoliberal restructuring of the university, hence presenting the university as yet another victim rather than an active participant in upholding coloniality. The colonial historiography and the dominant narration of the university continue to silence the past (Trouillot, 2015) while also ignoring the violent and colonial technologies produced by the university in the present that are used by settler-colonial states (Tabar & Desai, 2016; Turner, 2022). The university not only helps establish a colonial symbolic structure that legitimates physical violence beyond the walls of the ivory tower, but it also actively produces the colonial technologies used to displace Indigenous peoples. The recent grant given to Howard[ii]University by the secretary of defense seeking to “diversify” national security paints a clear picture of the democratization of domination where students of color in the Global North can also participate in the production of knowledge and technologies of violence used against people of color in the Global South (e.g., Palestine). The geopolitics of curriculum gestures toward the analysis and critique of these very real imperial projects in which higher education institutions form an integral part.

Situated historically, formal education institutions are understood as the central pillars upon which imperial/colonial projects are articulated at a global scale. They are geopolitically entangled whereby the curriculum and governance structures correspond to the broader political economic and sociocultural designs of the colonial matrix of power revolving around the central organizing principle of race. By interrogating the historicity, coloniality, and materiality of the university, one can avoid the tendency to critique the university merely as a symbolic or cultural institution (Turner, 2022). The university is responsible for much more when we make more visible and take more seriously its linkages to power and its geopolitical-economic implications within and beyond national boundaries.

Examining the university’s past and present colonial projects uncovers the master narrative upholding the so-called civilizing, modernizing, democratizing, and diversifying mission of higher education. Whether we take a close look at distinct higher education models used by previous colonial projects, we find that, although their political, cultural, and economic aims varied, they nonetheless became instrumental to colonial domination and capitalist exploitation. I contend that the university continues to serve as the cornerstone of coloniality as it not only legitimates dominant ways of knowing (symbolic structure) but also actively assists in the production of the material technologies needed to effectively dispossess communities. Making the university more inclusive is not what is at stake but rather the need to radically transform, if not dismantle the very colonial foundations of this institution. In other words, diversifying the content (symbolic or curriculum) will not change the geopolitical terms of the conversation (material power) within and beyond the university.

As Stein (2022) makes evident, it is necessary to counter the idealization of universities whereby they are conceived as fundamentally good institutions yet increasingly destabilized by neoliberal higher education reforms—victims of rather than complicit in domination and exploitation. The colonial foundations are hardly ever addressed when higher education curriculum is only seen through contemporary lenses drawing on critiques of neoliberalism since the 1970s. By historicizing higher education curriculum against the backdrop of colonialism and coloniality, a different picture is painted of its “structural complicity in racial, colonial, and ecological violence” (p. 4). I argue that the geopolitics of curriculum has perpetuated the modern/colonial capitalist world system since the 16th century. Without seriously interrogating the geopolitics of curriculum, it would be difficult to understand, for instance, the effectiveness of Spain’s political, economic, and religious institutions in maintaining the colonial order intact throughout a region as vast as Latin America and the Caribbean. Moreover, it would be difficult to examine the neoliberal economic restructuring of the region without also interrogating the role of the curriculum. Sidelining the geopolitical colonial project of the curriculum will only naturalize colonial domination and capitalist exploitation. In other words, it would erase the dialectical relationship between knowledge and power and the dominant subjectivities reproduced through the pedagogies of domination constitutive of educational institutions. Understood as a canonizing and homogenizing geopolitical instrument of power, the curriculum thus reproduces the dominant subjectivity necessitated to effectively maintain neocolonial and settler colonial social arrangements.

The university curriculum continues to be complicit in reproducing colonial power and hence is responsible for sustaining asymmetrical social relations of power. Its aim is the systematic canonization of knowledge and thus the erasure of Indigenous systems of knowledge, images of the world, collective memories, and aesthetics. The coloniality of curriculum upholds an epistemology of ignorance (Mill, 1997) that systematically prescribes absence whereby nothing else could exist outside of the Eurocentric canon, narrative, and teleology; no “counter-voice” could be allowed to speak (Wynter, 2003, p. 269). The curriculum instead continues to produce “administrators, educators, professionals,…and other wielders of pen and paper” (Rama, 1996, p. 18). Neocolonialism in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as in other continents, is contingent upon learned individuals, usually from the dominant ethnoclass, who effectively wield their power from the lettered cities (universities) of the region. The university curriculum plays a central role in creating the subjectivities that would enable other institutions to run smoothly according to colonial designs and racialized social arrangements. Without the complicity of the university and its geopolitically implicated curriculum and pedagogy of cruelty, the domination of a region as vast as Latin America and the Caribbean would be inconceivable. Therefore, the curriculum is intimately linked to the geopolitical economic project of modernity/coloniality, and it positions the Eurocentric subject as the only subject worthy of speaking, thinking, knowing, and existing. Other histories, knowledges, and experiences are ontologically insignificant.

Honduras is a specific case to consider when thinking about the longue durée of the geopolitics of curriculum. Liberal curriculum reforms in the 19th century were implemented according to the geopolitical economic reconfiguration of the modern/colonial world, which witnessed the United States as an emerging imperial power in the Western Hemisphere. The liberal education reforms included in the national constitution of 1880 and the Code of Public Instruction of 1882 complemented the liberal economic reforms initiated in 1876 (Fúnez-Flores, 2020). In addition to opening Honduras to US mining companies, these reforms set the stage for the creation of a geopolitically important neocolonial “Banana Republic” under the control of the United Fruit Company (Chiquita Brands International) and the Standard Fruit Company (Dole Food Company). Both reforms created the conditions for the sociopolitical and economic conflicts that ensued throughout the 20th century in Honduras as well as in Central America (Barahona, 2005). Curriculum reform adopted a positivist philosophy of education that completely removed all knowledge from the education system that was not instrumentally aligned to the knowledge, skills, and commodities demanded by foreign capitalist interests. The positivist curriculum aligned itself with a monocultural and extractivist economy that would meet the increasing demands of the US. Economic and education reforms in Honduras in the late 19th century reveal the intimate relationship the university curriculum began to have with the economic demands of emerging powers such as the United States. More importantly, these reforms can be conceptualized as curriculum epistemicides[iii] and reversive epistemicides (Paraskeva, 2016), which enabled the reconstitution or reconfiguration of coloniality through the violent destitution of other ways of knowing.

If we fast forward to the 21st century, we find the implementation of neo-developmental policies concomitant with neoliberal discourses aimed at restructuring the global economy into one that is primarily knowledge-based (Torres, 2009; Torres & Schugurensky, 2002). A knowledge-based economy positions the university not only as a producer of a specific type of knowledge but also as an invaluable agent of neoliberal globalization. Under this shifting geopolitical economic landscape, one observes a strong relationship between neoliberalism, higher education reform, and coloniality. In addition to being ideological and cultural, contemporary higher education curriculum reform cloaked under the guise of a so-called global knowledge economy is linked to a colonizing process seeking to meet the material demands of the Global North. When knowledge is conceived as global, it creates the illusion that it benefits everyone equally, while neo-developmental, tourist, and service industry projects continue displacing Indigenous, Afro-Indigenous, Black, and campesino communities with the assistance of the university. In contrast to “global” knowledge, the “local” is portrayed as parochial and less worthy of forming part of the curriculum, which reproduces the Eurocentric dualist ontology that separates the modern (universal) from the traditional (particular). Dominant ways of knowing cannot be stripped away so easily from their complicity in maintaining asymmetrical relations of power. A global knowledge economy universalizes and naturalizes itself at the expense of all knowledges and ways of knowing that fall outside of its narrow capitalist parameters. One should ask whose knowledge we are learning or, better yet, consuming. Whose futures are foreclosed through said knowledge? Who benefits?

Although there is limited space to discuss how these questions are being explored by sites of struggle, namely student movements in the region (Fúnez-Flores, 2020), it is important to note that they are collectively creating educational spaces and politically organizing to radically democratize university governance structures and curriculum reform. Their way of organizing horizontally through public assemblies, workshops, popular education, social media, and WordPress publications gesture toward possible ways to unsettle the university in material and symbolic terms. Using Quijano’s intricately relational understanding of heterogeneity and coloniality, one can also reveal how the local resistance against curriculum reform and neoliberal governance structures is not parochial but is rather a collective movement against the global designs upholding coloniality.

Final Thoughts

As discussed throughout this article, the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum are operationalised geopolitically and weaponised pedagogically to construct a dominant subjectivity. It is evident that the canon has always been a close companion of the cannon. As Toni Morrison (1988) expressed, ‘Canon building is empire building. Canon defense is national defense’ (p. 132). As the Honduran case above suggests, the curriculum has always been geopolitically tied to imperial/colonial projects. The cannon leads to material destruction and physical subjugation (Thiong’o, 1981), while the canon leads to symbolic destruction and spiritual, cultural, and epistemic subjugation justifying the former. Both are entangled processes and implicated in colonial domination.

Following Quijano’s relational, entangled, and heterogeneous understanding of the material and symbolic dimensions of coloniality, I have argued that modern/colonial ideas, concepts, theories, methodologies, pedagogies, histories, aesthetics, values, affects, ways of knowing, sensing, being, and relating are all embedded in and reproduced by the dominant curriculum within and beyond the nation-state. The geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum are thus an enduring violent pedagogical act that systematically subjugates and destroys other interpretations to the degree in which the colonised Other views and interprets the world through the coloniser’s eyes, conceptual networks, theoretical frameworks, hermeneutics, methodologies, aesthetics, and ontological assumptions. The images reflected by these distorted lenses are precisely the negative representations of Others (Fúnez-Flores, 2021), that is, of those on the receiving end of coloniality. In previous sections, I have made evident that structural and discursive power are intimately intertwined, thereby co-producing one another. As Wynter (1992) cogently expressed, ‘To be effective, systems of power must be discursively legitimated. This is not to say that power is originally a set of institutional structures that are subsequently legitimated. On the contrary, it is to suggest the equiprimordiality of structure and cultural conceptions in the genesis of power’ (Wynter, 1992, p. 65). Decolonial thought in general and Quijano’s work, in particular, emphasizes this equiprimordiality by unravelling modernity’s colonial material-symbolic entanglements, while pointing to the existence and emergence of heterogeneity despite the longue durée of coloniality.

The geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum function as a technology of control and management of knowledge within a broader, more extensive, planetary context. It is linked to the colonial matrix of power and social totality in which symbolic (cultural, curricular, and epistemic) and material/structural colonial domination and capitalist exploitation are co-constituted. In this sense, the coloniality of curriculum is geopolitically entangled insofar as it is strategically deployed to prevent the recovery of systematically excluded histories[iv], memories, stories, knowledges, practices, and struggles against colonialism, racism, capitalism, and heteropatriarchy across distinct yet historically interconnected geographies (Lowe, 2015). Although coloniality tries to destroy collective memories to distort our understanding of the modern/colonial order of things, student, youth, Indigenous, Afro-Indigenous, Black, feminist, and peasant movements are organizing to collectively reclaim, live, and embody our histories and struggles to prefigure our decolonial futures in the present (see, e.g., Fúnez-Flores et al., 2022; Muñoz Garcia et al, 2022; Peña-Pincheira & Allweiss, 2022; Pinheiro-Barbosa, 2022, Sorzano, 2022).

Decolonization/decoloniality is an act of refusal transformed into a life-affirming (geo)political act (Simpson, 2007; Tuck & Yang, 2014). As Mbembe (2021) suggests, it is ‘a struggle by the colonized to reconquer the surface, horizons, depths, and heights of their lives….an act of rebellion turned into an act of refoundation’ (p. 44). The problem with decolonization or decoloniality, however, is that these terms have become the property of academics who tend to empty these concepts of their geopolitical and liberatory content, including collective modes of resisting, organizing, and producing knowledge from below. To reclaim our histories, stories, and memories implies situating the curriculum in sites of struggle. A counter-curriculum is needed to challenge the modern/colonial system of signification maintained by coloniality. Students collectively challenging modern/colonial (dis)courses are usually those who are punished, silenced, and disappeared in Latin America and the Caribbean, for instance, yet these acts of rebellion create small cracks in a system that appears unbreakable. As Wynter (1992) observes, we must refuse or ‘fail to stay the course by violating the central interdiction’ of modernity that configures our subjectivities according to colonial and colonising desires (p. 64).

Despite systematic erasures, there exists a paradox in any system of domination. In other words, resistance often appears in spaces we least expect. Schools and universities, for instance, became places of molecular resistance for Indigenous and Pan-African movements linked to decolonisation. As Yang (2017) so clearly demonstrated, the paradox of coloniality is that symbolic and material resistance emerges within colonial spaces, namely in colonial institutions such as schools and universities (e.g., Indigenous students resisting in boarding schools and Pan-Africanist student intellectuals in universities situated in the Global North). Although the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum is a ‘behavior-regulatory inferential system of meanings’ that constitutes the modern/colonial world symbolically and materially (Wynter, 1990, p. 358), there are moments of resistance and re-existence revealing the limitations of imposed systems. While the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum depend on the metaphysical and pedagogical imperative of negating others the right to live with dignity, is it not also true that students, Indigenous, Black, Latinx, peasant, and Afro-Indigenous communities have always resisted their dehumanisation by articulating counter-discourses and practices? Is it not also true that resistance is also accompanied by re-existence, that is, by affirming reciprocal ways of being and relating? Decolonial theory, as advanced by Quijano, happens to be one of many counter-discourses and interpretive lenses that enable us to interrogate and unlearn the many ‘truths’ taught to us by educational institutions while uncovering and reclaiming other truths hidden by the curriculum.

As organic intellectuals committed to unsettling colonial domination, we must critically examine the socio-systemic reality of modernity/coloniality. We must also challenge the notions that we cannot delink ourselves from the historically complicit and ‘intellectually indentured intelligentsia’ incapable and unwilling of directing their theories toward the geopolitical (Wynter, 1990, p. 365). From Wynter and Quijano, we learn that it is imperative to dismantle the ascription and re-articulation of race, its regulatory meaning-making function, and the social pyramid it has configured globally since 1492. Although the silencing of the past by the coloniality of curriculum is not new, there are moments when the deafening silence of the past is interrupted by those on the receiving end of domination.

Quijano invites us to escape this prison by thinking of decoloniality in liberational, relational, epistemological, and intercultural terms: ‘The liberation of intercultural relations from the prison of coloniality also implies the freedom of all peoples to choose, individually or collectively, such relations: a freedom to choose between various cultural orientations, and, above all, the freedom to produce, criticize, change, and exchange culture and society” (Quijano, 1991/2007, p. 178). Decoloniality is, finally, a relational and ethico-political praxis aimed at replacing vertical understandings of the global with horizontal understandings of the planetary, which demands an ethic of reciprocity, relationality, communality, conviviality, and convivencia (co-existence) with others and the world. It is an affirmation of life.

References

Ahmed, S. (2014). Cultural Politics of Emotion. Routledge.

Andreotti, V. (2011). (Towards) decoloniality and diversality in global citizenship education. Globalisation, Societies and Education: The Political Economy of Global Citizenship Education, 9(3–4), Article 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2011.605323

Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Pashby, K., & Nicolson, M. (2016). Social cartographies as performative devices in research on higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1125857

Barahona, M. (2005). Honduras en el siglo XX: Una síntesis histórica. Editorial Guaymuras.

Baszile, D. T. (2019). Rewriting/recurricularlizing as a matter of life and death: The coloniality of academic writing and the challenge of black mattering therein. Curriculum Inquiry, 49(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2018.1546100

Bhambra, G. K. (2014). Postcolonial and decolonial dialogues. Postcolonial Studies, 17(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2014.966414

Blaut, J. (1993). The Colonizer’s Model of the World: Geographical Diffusionism and Eurocentric History. Guilford Press.

Bonilla, Y. (2020). The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA. Political Geography, 78, 102181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102181

Carter, L. (2008). The armchair at the borders: The “messy” ideas of borders and border epistemologies within multicultural science education scholarship. Science Education, 94(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20323

Castro-Gómez, S., & Grosfoguel, R. (2007). El giro decolonial: Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global. Siglo del Hombre Editores : Universidad Central, Instituto de Estudios Sociales Contemporáneos Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Instituto de Estudios Sociales y Culturales, Pensar.

Clayton, A. (2023, January 20). Ron DeSantis bans African American studies class from Florida high schools. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/jan/19/ron-desantis-bans-african-american-studies-florida-schools

De Lissovoy, N. (2010). Decolonial pedagogy and the ethics of the global. Discourse, 31(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596301003786886

Díaz Beltrán, A. C. (2018). The nowhere of global curriculum. Curriculum Inquiry, 48(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2018.1474712

Dussel, E. (1980). Filosofía de la liberación. Universidad Santo Tomás, Centro de Enseñanza Desescolarizada.

Escobar, A. (2007). Worlds and knowledges otherwise: The Latin American modernity/coloniality research program. Cultural Studies, 21(2/3), Article 2/3.

Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth. Grove Press.

Gandarilla Salgado, J. G., García-Bravo, M. H., & Benzi, D. (2021). Two Decades of Aníbal Quijano’s Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism and Latin America. Contexto Internacional, 43, 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2019430100009

Gilmore, R. W. (2022). Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation. Verso Books.

Glissant, É. (1997). Poetics of Relation. University of Michigan Press.

Gonzáles Casanova, P. (1987). Historia y sociedad. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Gramsci, A. (1999). Selections from Prison Notebooks (Q. Hoare & G. Nowell-Smith, Eds.). Lawrence & Wishart.

Grosfoguel, R., Hernández, R., & Velásquez, E. R. (2016). Decolonizing the Westernized University: Interventions in Philosophy of Education from Within and Without. Lexington Books.

Grosfoguel, R. (2007). The epistemic decolonial turn: Beyond political-economy paradigms. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), Article 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162514

Gross, T. (2022, February 3). From slavery to socialism, new legislation restricts what teachers

can discuss. NPR.

https://www.npr.org/2022/02/03/1077878538/legislation-restricts-what-teachers-can-discuss

Guzmán, A. (2019). Descolonizar la memoria: Descolonizar los feminismos. Tarpuna Muya.

Jaramillo, N. E. (2015). The art of youth rebellion. Curriculum Inquiry, 45(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2014.995064

Jaramillo, N. E. (2012). Occupy, Recuperate and Decolonize. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies (JCEPS), 10(1), 67–75.

Jaramillo, N. (2012). Immigration and the challenge of education: A social drama analysis in South Central Los Angeles. Springer.

Jaramillo, N., & McLaren, P. (2008). Socialismo Nepantla and the Specter of Che. Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies, 191.

Jivraj, S., Bakshi, S., & Posocco, S. (2020). Decolonial trajectories: Praxes and challenges. Interventions, 22(4), 451-463.

Kanji, A., Palumbo-Liu, D., & Bacchetta, P. (2021). In solidarity with French academics targeted by the republic | Opinions | Al Jazeera. AlJazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/4/12/in-solidarity-with-french-academics-targeted-by-the-republic

Lander, E. (1999). ¿Conocimiento para que? ¿Conocimiento para quien? Reflectiones sobre la universidad y la geopolitica de los saberes hegemonicos. Estudios Latinoamericanos, 7(12), 25–46.

Leonardo, Z., & Porter, R. K. (2010). Pedagogy of fear: Toward a Fanonian theory of ‘safety’in race dialogue. Race Ethnicity and Education, 13(2), 139-157.

Lowe, L. (2015). The Intimacies of Four Continents. Duke University Press.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21(2 3), Article 2 3.

Mariátegui, J. C. (2007). Siete ensayos de interpretación de la realidad peruana. Fundación Biblioteca Ayacucho,.

Mbembe, A. (2021). Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization. Columbia University Press.

McLaren, P., & Jaramillo, N. E. (2010). Not neo-Marxist, not post-Marxist, not Marxian, not autonomist Marxism: Reflections on a revolutionary (Marxist) critical pedagogy. Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 10(3), 251-262.

McLaren, P., & Jaramillo, N. E. (2006). Critical pedagogy, Latino/a education, and the politics of class struggle. Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 6(1), 73-93

Mignolo, Walter (2021). The politics of decolonial investigations. Duke University Press.

Mignolo, W. (2000). Local histories/global designs: Coloniality, subaltern knowledges, and border thinking. Princeton University Press.

Mills C. W. (1997). The racial contract. Cornell University Press.

Morrison, T. (1988). Unspeakable Things Unspoken: T he A fro-American Presence in American Literature. Michigan Quarterly Review, 28(11), 123-163.

Paraskeva, J. M. (2016). Curriculum epistemicide: Towards an itinerant curriculum theory. Routledge.

Paraskeva João M. (2016). The curriculum: whose internationalization? Peter Lang.

Paraskeva, J. (2013). Whose internationalization?. Journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Curriculum Studies (JAAACS), 9(1).

Paraskeva João M. (2011). Conflicts in curriculum theory : challenging hegemonic epistemologies. Palgrave Macmillan.

Pinar, W. (2004). What is curriculum theory? L. Erlbaum Associates.

Pinar, W. (2006). Internationalism in curriculum studies. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 1(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15544818ped0101_6

Patel, S. (2017). Colonial modernity and methodological nationalism: The structuring of sociological traditions of India. Sociological Bulletin, 66(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022917708383

Pratt, M. L. (2022). Planetary Longings. Duke University Press.

Quijano, A. (1981). Sociedad y Sociologia en América Latina. Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 1(2), 223–249.

Quijano, A. (1988). El estado actual de la investigación social en América Latina. Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 3(4), 155–169.

Quijano, A. (1989a). La nueva heterogeneidad estructural de América Latina. In H. Sonntag (Ed.), Nuevos temas nuevos contenidos? Las ciencias sociales de América latina y el Caribe en el nuevo siglo (pp. 8–33). UNESCO.

Quijano, A. (1989b). Paradoxes of Modernity in Latin America. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 3(2), 147–177.

Quijano, A., Clímaco, D. A., & Quijano, A. (2014). Cuestiones y horizontes: De la dependencia histórico-estructural a la colonialidad/descolonialidad del poder: antología esencial (Primera edición). CLACSO.

Quijano, A. (1992). Americanity as a concept, or the Americas in the modern world-system. International Social Science Journal, 44, 549–558.

Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power and eurocentrism in Latin America. International Sociology, 15(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580900015002005

Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353

Restrepo, E., & Escobar, A. (2005). ‘Other anthropologies and anthropology otherwise.’ Critique of Anthropology, 25(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X05053009

Rose, E. (2019). Neocolonial mind snatching: Sylvia Wynter and the curriculum of man. Curriculum Inquiry, 49(1), 25-43.

Sachs, J. (2022, January 24). Steep rise in gag orders, many sloppily drafted, PEN America.

https://pen.org/steep-rise-gag-orders-many-sloppily-drafted/

Segato, R. L. (2018). A manifesto in four themes (R. McGlazer, Trans.). Critical Times, 1(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1215/26410478-1.1.198

Shahjahan, R. A., Estera, A. L., Surla, K. L., & Edwards, K. T. (2022). “Decolonizing” Curriculum and Pedagogy: A Comparative Review Across Disciplines and Global Higher Education Contexts. Review of Educational Research, 92(1), 73–113. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042423

Shahjahan, R. A. (2016). International organizations (IOs), epistemic tools of influence, and the colonial geopolitics of knowledge production in higher education policy. Journal of Education Policy, 31(6), 694–710.

Sibai, S. A. (2018). La cárcel del feminismo: hacia un pensamiento islámico decolonial. Ediciones Akal

Simpson, A. (2007). On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship. Junctures: The Journal for Thematic Dialogue

Stein, S. (2022). Unsettling the University. Princeton University Press.

Stein, S. (2021). What Can Decolonial and Abolitionist Critiques Teach the Field of Higher Education? Review of Higher Education, 44(3)

Streck, D. R., & Adams, T. (2012). Research on education: Social movements and epistemological reconstruction in a context of coloniality. Educação e Pesquisa, 38, 243-258.

Sultana, F. (2022). The unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality. Political Geography, 102638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

Tabar, L., & Desai, C. (2017). Decolonization is a global project: From Palestine to the Americas. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 6(1). i-xix

Thiong’o, N. W. (1981). Decolonizing the mind: The politics of language in African Literature, Harare.

Torres. (2009). Education and neoliberal globalization. Routledge.

Torres, & Schugurensky. (2002). The political economy of higher education in the era of neoliberal globalization: Latin America in comparative perspective. Higher Education, 43(4), 429–455. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015292413037

Trouillot, M. R. (2015). Silencing the past: Power and the production of history. Beacon Press.

Turner, K. (2022). Disrupting Coloniality Through Palestine Solidarity. Interfere, 3, 6-34.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2014). Unbecoming Claims: Pedagogies of Refusal in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 811–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530265

Wynter, S. (1990). Afterword: “Beyond Miranda’s Meanings: Un/Silencing the ‘Demonic Ground’ of Caliban ‘Woman.’” In Out of the Kumbla Caribbean Women and Literature (pp. 355–370). Africa World Press.

Wynter, S. (1992). Beyond the Categories of the Master Conception: The Counterdoctrine of the Jamesian Poiesis. In C. L. R. James’s Caribbean (pp. 63–91). Duke University Press.

Wynter, S. (2003). Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/truth/freedom: Towards the human, after man, its overrepresentation—An argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), Article 3.

Zembylas, M. (2021). Sylvia Wynter, racialized affects, and minor feelings: Unsettling the coloniality of the affects in curriculum and pedagogy. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1946718